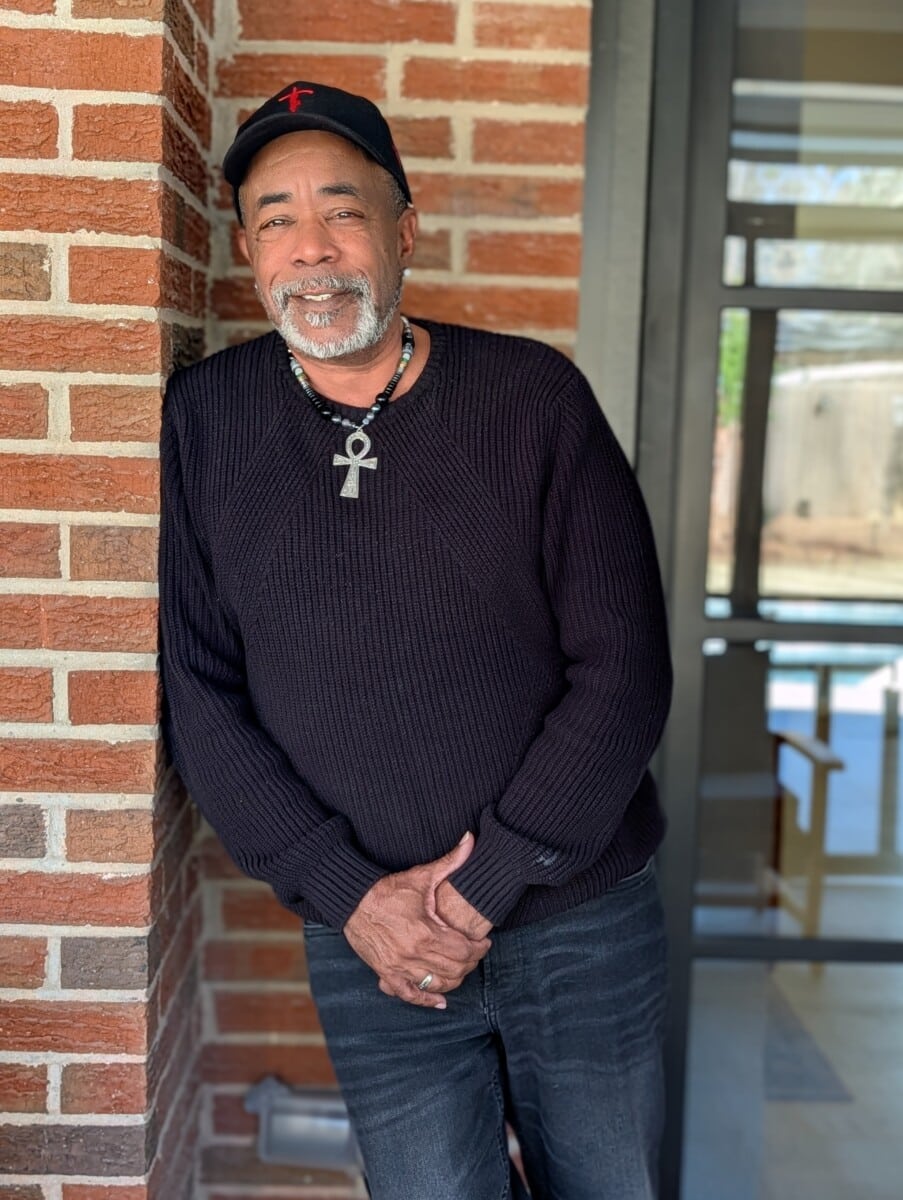

Malcolm Reid has the X Factor, a compelling way about him that attracts your attention but which you can’t quite put your finger on. Saying so about him would probably make him grin and even blush, which only makes the case for his charms even stronger.

Malcolm is 68 years old and lives in Decatur, Georgia. Diagnosed with HIV in 1996 (but knowing his status for years; more on that soon), Malcolm entered the HIV arena as an advocate in 2015. His maturity and the easy way he parcels out wisdom might lead you to believe he has been in the trenches much longer.

Malcolm has kept himself busy in his decade of service. In 2015 he got involved with THRIVE SS, lifting up gay Black men. He launched the Silver Lining Project for older gay Black men living with HIV. He founded his own company, Unity Arc Advocacy Group. He is part of the development of an online tool to help link people into care.

And now, Malcolm is the newly installed co-chair, with Michael Elizabeth, of the U.S. People Living with HIV Caucus (aka The Caucus).

My lively conversation with Malcolm covered his HIV journey, racism, aging, and dealing with shame and toxic masculinity.

Here is our conversation, gently edited for length and clarity.

Mark S. King: Tell me about your HIV diagnosis.

Malcolm Reid: In 1991, my lymph nodes were swollen. I remember that night vividly. I was living in midtown Atlanta and read this article in Ebony magazine about a Black man who had swollen lymph nodes. My mom was a nurse, so I ran to a phone booth and called. This was 11 o’clock at night. I was crying. I told her about the article, and that I thought I had AIDS. Mom said, “Calm down, and here’s what you need to do. Go get it checked but don’t let them give you any medication.” She worked at Planned Parenthood, so as a community health clinic, they were seeing people with HIV. They were treated with AZT.

Which was problematic then.

I tell people my mother saved me from AZT.

Why didn’t you take the actual test then?

I kinda knew. The doc I saw about the lymph nodes said my symptoms were “consistent with HTLV3.” Then in ‘96, when the protease inhibitors started and meds were getting better, I went to my doctor and said I needed to get tested for HIV. He said, “Why?”

That’s an interesting question for the doctor to ask.

Yeah. He came back and said the test came back positive. I wasn’t surprised. Anyway, they put me on combination therapy.

And did that work right away?

Yes. Got my viral load under control, but I had side effects. Shortly after that, I met Stewart, who became my boyfriend and later my husband. Talk about side effects. We would go on vacation and we were both on Viracept, and we would go to breakfast in the morning and go back to our hotel room and wait to see who had to go to the bathroom first. Whoever was second might have to go to the lobby in the hotel.

How romantic.

Yeah! Then my doctor moved and I got a new one. I read that I should stop the Viracept because of the side effects, and the doctor was alarmed about that. I told him about what I read and he left the room and came back after doing some research and said I was right.

That’s a great example of an empowered patient.

That’s why I tell the story.

I’m always interested in how racism permeates every aspect of our lives, and HIV is no different. What do white folks keep getting wrong when it comes to race and HIV?

White folks assume Black folks did it to themselves, as opposed to gay white men getting sympathy, like, “I’m so sorry that happened to you.” In one case, they did it to themselves. In the other case, people are sorry that happened to you.

So it’s a blame game that’s fixed in favor of white men. Do a lot of Black men internalize that?

Oh yeah. There are a lot of Black men who contract HIV and blame themselves. Because society has taught them to blame themselves, which is why suicide rates are higher in the Black community.

Do you see that changing?

I do see it changing. I think young Black gay men know about HIV status and being undetectable. It’s definitely more accepted. People put their status on apps.

I’m so impressed with this new generation of gay Black men on the scene. These younger guys who are kicking ass and moving up in the ranks into positions of leadership. I call them the Black Nouveau.

I agree. I’m absolutely thrilled. Men like Darwin Thompson, Deondre Moore, Daniel Driffin, doing the work and using their education.

And a lot of them have no idea who survivors like me are, not that it matters. They have too much work to do!

When dealing with younger people, I always try to go back to when I was young. I was proud and thankful for what my elders had accomplished, but I was able to think more progressively. I am excited about some of the things I see.

I saw you at a conference last year and remember watching you hold court. You were settled in a lounge chair and you didn’t move for ages because of this line of handsome young Black men talking to you and paying their respects. It made me smile.

I just want them to know that I respect them, too. I love them. I want them to succeed. I never scold them. And a smile and a hug goes a long way. I do know that when I say something people listen. So I don’t say stupid shit.

It took so long for me to shed the need to project the kind of hyper-masculinity that gay culture craves. Do gay Black men feel that more acutely?

I lived with that pressure for years. When my dad left I was 8. He said, “You’re the man of the house now.” That was the most traumatic part of coming out in the housing projects of New York. I realized that you couldn‘t be gay, and you couldn’t be feminine. There are still people who equate being a top with being a man. This crosses racial barriers. I call it the Ward and June Cleaver gay relationships. Because if you’re the bottom, you’re June.

I love you referencing classic white TV. Speaking of 60-year old television, we’re both men of a certain age. I’m 65 and you’re 68. Aging is strange. How is it going for you?

Well. I think the work that I do helps me deal with it better. I know the issues, whether it be medically, mentally or physically.

You also have a sense of purpose. I think that helps.

Yes, and it’s information. Having the information has helped me deal with all those things. And I have been blessed to have Stewart in my life for the last 28 years and to go through this together.

The two of you have the cutest, most romantic postings on social media of any couple I know. I’m just saying.

I appreciate that.

You’ve picked one hell of a time to become co-chair of a national advocacy group. Tell me more about the U.S. People Living with HIV Caucus, aka The Caucus. It is a collection of organizations that each represent people living with HIV. Do I have that right?

Yes. It is a network of networks. Positive Women’s Network USA, The Sero Project, Reunion Project, etc. The mission of the caucus is to abolish systems of oppression that affect PLWHA. We envision a world in which people with HIV have everything they need to thrive. We also have individual members, not just networks.

So anyone living with HIV could join as an individual member.

Right. Our main goal is to make sure government policy, and organizations representing people living with HIV, are MIPA (Meaningful Involvement of People with HIV/AIDS) centered. We’re a force multiplier. And we do have a few programs, educating our members and advocacy on their behalf. Some of us are working on the #SAVEHIVFUNDING project, others on addressing this administration trying to kill all funding related to HIV. We’re an all volunteer organization.

That’s a lot. There’s a political advocacy project being organized right now that is focusing on June 2026, around the 45th anniversary of the first report of what would become HIV/AIDS, to organize the HIV community to become active in their 2026 primary elections. We all need to reignite the kind of activism about which we are known, back in the day.

Definitely, Something I mentioned in the Caucus strategy meeting is that we are under attack. It’s nice to write a sign-on letter, policy positions, etc., but we need to be a little more activism oriented. Educate, advocate, and agitate. Advocacy is wonderful, but every now and then we need to agitate.

This is one of those times.

Definitely. Those people in the streets of Minneapolis, ACT UP, Black Lives Matter, all that has got to be a part of what we do as the Caucus. If we don’t get what we want, we’re not going to be so polite. At some point, we have to say, fuck this, we’re going to get in the streets and do whatever we need to do to be heard.

Amen.