(I will never explain the early days of AIDS better then this, so I post this essay to commemorate World AIDS Day every year. This essay, written in 2007 for Southern Voice newspaper, won “Outstanding Opinion Piece” from NLGJA, the national LGBTQ journalism association.)

My brother Richard smiles a lot. He has an easy laugh. But there was a time, years ago, when he held a poisonous drink in his hands and begged his dying lover not to swallow it. A time when Richard held the concoction they had prepared together and wept.

Emil couldn’t wait. He took the drink from Richard quickly, because the release it offered was something more rapturous than the appeals of his lover of thirteen years.

It was Emil’s wish to die on his own terms if living became unbearable, a promise made one to the other. When that time arrived, however, Richard wanted another moment, just a little more time to say, “I love you, Emil,” over and over again, before the drink would close Emil’s eyes and quietly kill him.

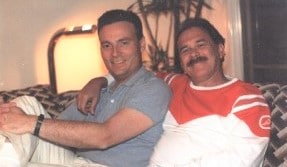

Richard has a charming store in my hometown today, where he sells collectibles and does theater in his free time. The drink was consumed more than thirty years ago.

Richard King today

There were people who displayed remarkable courage then. People who lived and died by their promises and shared the intimacy of death, and then the world moved forward and grief subsided and lives moved on. But make no mistake, there are heroes among us right now.

There is a shy, friendly man at my gym. There was a time when his sick roommate deliberately overdosed after his father told him that people with unspeakable diseases will suffer in hell. My gym friend performed CPR for an hour before help arrived, but the body never heard a loving word again.

There is courage among us, astonishing courage, and we summoned it and survived. And then years passed. We got new jobs and changed gyms.

There was a time when old friends called to say goodbye, and by “goodbye” they meant forever. When all of us had a file folder marked “Memorial” that outlined how we wanted our service to be conducted. When people shot themselves and jumped off bridges after getting their test results.

There is profound, shocking sadness here, right here among us, but years went by and medicine got better and we found other lives to lead. Our sadness is a distant, dark dream.

My best friend Stephen just bought a new condo. He’s having a ball picking out furniture. But there was a time when he knew all the intensive care nurses by name. When a phone call late at night always meant someone had died. And just who, exactly, was anyone’s guess.

Stephen tested positive in the 1980s, shortly after I did. A few months after the devastating news, he agreed to facilitate a support group with me. We regularly saw men join the group, get sick and die, often within weeks.

Watching them disintegrate felt like a preview of coming attractions. But Stephen was remarkable, a reassuring presence to everyone, and worked with the group for more than a year despite the emotional toll and the high body count.

There is bravery here, still, living all around us. But the bravest time was many years ago, and times change and the yard needs landscaping and there’s a brunch tomorrow.

There was a time when I sat beside friends in their very last minutes of life, and I helped them relax, perhaps surrender, and told them comforting stories. And lied to them.

Jeremy lost his mind weeks before he died. Sometimes he had moments of sanity, when we could have a coherent conversation before his dementia engulfed him again. It was a time when you were given masks and gloves to visit friends in the hospital.

He was agitated with the business of dying, and told me he couldn’t bear to miss what might happen after he’d gone. I had an idea.

“I tell you what,” I offered, “I’m from the future, and I can tell you anything you would like to know.”

“OK then, what happens to my parents?” he asked. I thought it might be a distracting game, but Jeremy’s confused mind took it very seriously.

“They went to Hollywood and won big on a game show, so they never did need your support in their old age,” I answered. He barely took the time to enjoy this thought before his hand grabbed my wrist, tightly, almost frantically. He pulled me closer.

“When…” he began, and a mournful sob swelled inside him in an instant, his eyes begging for relief. “When does this end?” There was an awful, helpless silence. His eyes beckoned for a truth he could die believing.

“It does end,” I finally managed, although nothing suggested it would. “It ends, Jeremy, but not for a really long time.” He digested each word like a revelation, and slowly relaxed into sleep.

There is compassion here, enough for all the world’s deities and saints acting in concert. Infinite compassion for men who lived in fear and checked every spot when they showered for Kaposi sarcoma, and for disowned sons wasting away in the guest room of whoever had the space. But we get older, and friends don’t ask us to hold their hand when they stop breathing, and the fear fades and I bought new leather loafers and the White Party is coming.

The truth is simply this, and no one will convince me otherwise: My most courageous self, the best man that I’ll ever be, lived more than two decades ago during the first years of a horrific plague.

He worked relentlessly alongside a million others who had no choice but to act. He secretly prayed to survive, even above the lives of others, and his horrible prayer was answered with the death of nearly everyone close to him.

To say I miss that brutal decade would only be partially true. I miss the man I was forced to become, when an entire community abandoned tea dances for town hall meetings, when I learned to offer help to those facing what terrified me most.

Today, the lives of those of us who witnessed the horror have become relatively normal again, perhaps mundane. We prefer it. We have new lives in a world that isn’t choking on disease.

But once, there was a time when we were heroes.

Mark

(This essay is included in my collection, My Fabulous Disease: Chronicles of a Gay Survivor.)