(This essay appears in my collection of essays, My Fabulous Disease: Chronicles of a Gay Survivor, available now at online outlets or your local bookstore.)

When my guard is down, it comes to me. It flashes across my mind, an uninvited assault, sometimes when I am beginning to drift off to sleep or, more cruelly, when my mind is enjoying a pleasant reverie. It is then that the dark memory rushes in like a raid.

He lived in a house with nice furnishings. That reassured me when I arrived for the hookup, given that so many of the other crystal meth addicts I encountered were barely holding on to the remnants of their lives. The others might have a sofa to offer — just move those clothes and dishes and don’t worry about the barking in the other room he’ll stop I promise – and a laptop computer, the only real necessity, anyway, so we could watch porn or troll for other tweakers who were up at this time of night.

Time, after all, is a quaint and needless concept to addicts searching for drugs and companionship. Like the weather, say, or our integrity.

He is sitting across from me and we are naked. Seconds earlier, we had both injected ourselves with meth. The pounding rush of the drug is in full force and the possibilities feel endless. I’m looking forward to the sexual promises we had made to one another when we chatted online. Desperately. Now.

But even in my delirium, I have the feeling that something is off. I am blinking through watery eyes and have begun to focus on him. He is staring at me, his gaze fixed with an intense and completely unexpected contempt.

And there is a gun in his hand. A gun a gun a gun a gun.

“You’re not who you say you are,” he says, softly and suspiciously. He trembles from the impact of the meth. As he speaks, the gun the gun the gun is moving this way and that, pointed mostly in my direction.

I have no response. I don’t know what he is capable of, or if the gun is loaded, if he will pull the trigger, if this is a sadistic sex game. I met the man maybe an hour ago. I wonder if you can die of fright.

I couldn’t know that this moment would keep me awake at night for years to come, or that it would create post-traumatic stress that would require therapy, or that the therapy would reveal the many times I put my life at risk during my years of addiction when I was too numbed to recognize danger, or that the realization of all of this would create such shame that I wouldn’t dare explain it to anyone, or that other dark memories from my drug use would continue to reveal themselves to me, popping up unannounced and uninvited.

“You didn’t even shoot up just now,” he says. He is sweating, and he wipes his brow with the back of his hand, the hand holding the gun the gun the gun.

“You just watched me do it,” I object, gently, nodding toward my spent syringe. I am working hard, so hard, to remain calm while my body shudders from the force of the drugs still streaming through me.

“You should go now,” he responds. He has not moved from his spot.

“Okay. I will do that,” I comply. Carefully, I step to my pile of clothes on the floor. “I’m so sorry this didn’t work out,” I offer, terrified of every word I choose, that something might provoke him. I wonder if I will hear the sound of the gunshot before I feel the impact.

I step into my shorts, make sure my keys and phone are inside, and grab my shirt. I must turn my back on him as I leave the room. I hear him walking behind me. My skin is prickling with terror. We make our way down a hall and out his front door. He stops there and waits silently.

I get into my car in the driveway and face him. He stands there, naked under the porch light, without regard for neighbors who might be awake during the dead of night. His arms are at his side but the gun the gun the gun is still pointed toward me. I am shaking so badly I am having trouble getting the keys into the ignition, like the frantic scene from a thousand horror movies.

My eyes dart back and forth, torn between backing out of the long driveway and watching the armed man standing on the porch. I finally manage to pull into the street and drive away, and then the panic hits me so hard I have to pull over to catch my breath. I sit there for half an hour, not knowing that I will bury this secret episode for a decade, keeping it from my friends and from people in recovery trying to help me. For all my transparency about my life with HIV and even my drug use, I would not know where to put this frightening event, how to reconcile it, when the fear and the shame will be lifted.

I will learn much later that these things take time. Addicts don’t recover at the same pace, in the same way. You can’t walk ten miles into the forest and expect to get out in five.

After my roadside break, I start the car again and drive directly to my drug dealer, the only person in the world who would welcome me in such a state. When my feet touch his gravel driveway I realize I am barefoot.

In a few moments, I will have more meth in my body to wipe away the trauma.

The meth the meth the meth the meth.

Mark

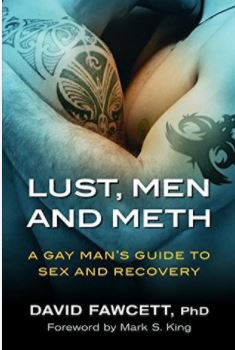

(If you or someone you care about might have a problem with crystal meth or other substances, get more information from Crystal Meth Anonymous, your local Narcotics Anonymous fellowship, or answer this questionnaire about your drug habits. I also highly recommend Lust, Men and Meth: A Gay Man’s Guide to Recovery by Dr. David Fawcett, Help is available. Recovery is possible.)

(If you or someone you care about might have a problem with crystal meth or other substances, get more information from Crystal Meth Anonymous, your local Narcotics Anonymous fellowship, or answer this questionnaire about your drug habits. I also highly recommend Lust, Men and Meth: A Gay Man’s Guide to Recovery by Dr. David Fawcett, Help is available. Recovery is possible.)

Photo: Uncredited photo of Mark S. King, (c) 2006