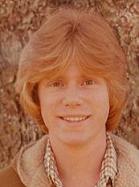

According to family lore, my arrival at birth with a full head of orange hair was met with shock and awe. My five older siblings ran the gamut from blond to dark brown, but they otherwise lacked my peculiar genetic mutation. Although the hospital nursery staff was abuzz with delight, my own family debated whether the color would last while they double checked the identification tags.

It lasted. In fact, the color bloomed like a Van Gogh painting. Before long I would learn the price of being different — and how intense childhood ridicule can be.

Look, it’s Freckle Face Strawberry! Howdy Doody. Bozo. Opie. I didn’t know whether to chop off my hair or hide underneath it. Only little old ladies and a few teachers seemed to appreciate it, but their cooing and stroking — they always needed to touch it, like a lucky charm — never endeared me to the bullies at school.

When puberty hit and the startling orange hue crept further down my torso I was beyond mortified. How could my body play such a cruel joke? Did this adolescent sissy really need another reason to be kicked and taunted? I actually made it through two years of junior high gym class without once taking a shower, usually by fiddling around at my locker — folding and arranging my clothes, feigning trouble with my combination lock — until it was safe to get dressed.

When puberty hit and the startling orange hue crept further down my torso I was beyond mortified. How could my body play such a cruel joke? Did this adolescent sissy really need another reason to be kicked and taunted? I actually made it through two years of junior high gym class without once taking a shower, usually by fiddling around at my locker — folding and arranging my clothes, feigning trouble with my combination lock — until it was safe to get dressed.

When I came bursting from the closet while in high school, I managed to finally celebrate my red hair along with my sexuality, and reveled in both. I mastered every hair product known to man, blow drying and spraying my head into a Farrah Fawcett extravaganza before a night out at the local gay bar. I discovered the men who loved redheads, and at last, I’d found the ideal purpose for the trait that once humiliated me.

It even became crucial to my vocation, during a brief stint in my twenties in television commercials. Casting directors saw dollar signs on my head, and I became the freckled pitchman for everything from McDonalds to Popeye’s to Barq’s root beer. I treated my hair as a gay Samson might, with the latest gels and shampoos and conditioners, and in return it made me money and got me laid.

Whatever I became through the years, this single aspect of my identity pre-dated everything. Before the writer, before the AIDS activist and the drug addict and the actor and the childhood sissy, I was a redhead. From the very womb.

And then, not quite. Sometime in my thirties, the color began to slowly drain from my scalp. The orange and reds eventually surrendered to a strawberry blond, and even those tones became weaker, like watering down a pitcher of Kool-Aid, as my fiftieth year approached.

It must sound ridiculous, but I felt the loss deeply. We had been through so much together, my red hair and I.

I tried to take heart in having, whatever the color, a full, thick head of healthy hair, guaranteed for life by the family gene pool. That is, until a few months ago, when I stood in the shower and felt strands of hair sliding down my face, in a massive march from my head to the drain. After decades taking HIV medications, I had begun a new treatment regimen and its woeful side effects were ruthless and immediate. Within weeks my hair was thinner, dulled and brittle to the touch.

One of my private, most selfish fears has been realized. I have AIDS Hair.

But while removing clumps from the shower drain is a jolt to my vanity, it isn’t the trauma it might have been. After living with HIV for nearly thirty years, I’ve witnessed how creative it can be in its cruelty, down to the slightest of indignities. The sudden damage to my hair has been worrisome, I’ll admit, but part of me knows that it had long since served its purpose. There is something correct, even poetic, in this twilight of the redhead.

Years ago, as I began rebuilding my life after years of drug addiction, my therapist made a withering observation. “You’ve got no second act, Mark,” he said after one of my self-absorbed ramblings. “You make a nice first impression. But then what? Not much.”

The work that I’ve done in the years since his pronouncement have taught me the value of more important traits, of lending a hand or paying attention to friends or standing up for our community. And this evolution appears to have swept away one of my most stubborn sources of willful pride.

The last decade has given me the gift of other, more meaningful assets. They lie beneath, away from the gaze of strangers and first impressions.

My best features are now visible only to those who really know me. And they are just beautiful.

Mark

(Since writing this five years ago, a change of medications has restored the health of my hair. Alas, age has taken away its earlier, neon hues. My beard today is the only feature that proves my redheadedness.)