(This originally appeared in THE ADVOCATE)

May 22, 2001

The descriptions of his decline, in whispered calls from back home, had a dreadfully familiar feel to them. Weight loss at a frightful pace. Losing interest in the world. Suddenly looking very old indeed. Most gay men of a certain age have heard those words, have seen the patient, have buried the friend. This case was different, though. It wasn’t AIDS, it was cancer. And the patient was Dad.

The disease had swept rapidly through my father since his initial diagnosis. The inevitable was approaching, but the territory was completely unfamiliar to my family, who hadn’t seen a death in more than 30 years. They were about to get a tour through hell. I have traveled it many times.

The disease had swept rapidly through my father since his initial diagnosis. The inevitable was approaching, but the territory was completely unfamiliar to my family, who hadn’t seen a death in more than 30 years. They were about to get a tour through hell. I have traveled it many times.

“Well, he’s lost a lot of weight,” Mom said on the phone, “and sometimes, he will say the same thing more than once. That does scare me a bit.” You think you’re scared now, I thought.

“Have you checked into hospice care?” I asked. It’s exhausting for a man in his 30s to care for a dying lover. Mom was 75.

“Well no, honey, I thought we could wait on that . . .” Her voice drifted.

Something inside me went on AIDS auto pilot.

“Call the doctor and ask about hospice care,” I practically ordered. “They can help avoid another hospital stay, Mom.” The family would do anything to prevent that scene again.

I flew home within days. Still no hospice care. My family was stunned into inaction, it seemed. Had anyone spoken to dad about getting nursing help, about his illness, about how everyone was dazed into speechlessness? Heads shook slowly, eyes looked downward.

After 15 years living with my own HIV infection, my medical choices — powers of attorney, “no resuscitation” instructions — had long been settled. Mom was uncomfortable with the decisions, much less the reality.

On my second day home, I found myself alone with Dad. He was bundled on the sofa, and whatever his thoughts, they seldom found words. His condition looked hauntingly familiar, leading me to a nonsensical conclusion. “Dad has AIDS,” my mind insisted.

“Can I talk to you about what’s going on?” I asked him.

“Yeah . . .?” he said weakly.

“This is really horrible Dad, and everyone . . . is freaked out and doesn’t know how to act.” His eyes never left me. “Mom is afraid to ask for help. You need a nurse . . . do you think that’s okay?”

“Well . . . yes. I do.” He meant it. “Your mother . . . your mother works very hard.” I took his hand. “This is hard for your mother, I think . . .” he continued. “Your mother and I . . . we are one mind, together. One mind.”

I had never heard anything so romantic from my father. He saw it in my face, and he found the sadness, too.

“Don’t worry,” he said, and his hand tightened around mine. “It’s okay. I’m all right. This is all right . . .”

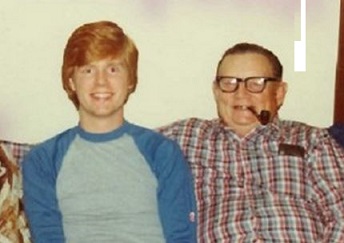

I wanted to say everything at once. Every declaration of love I had for my father, the retired Colonel who loved his family fiercely, laughed heartily, and equated only happiness with success.

“I will talk about you my whole life,” I said. “All the stories, all the things you’ve done for us . . . but how do I explain you to anyone?” My voice choked, and my attempt to properly organize my father’s last days was awash in unexpected tears.

I looked up and was stunned to see damp eyes staring back at my own. A tear escaped and rolled tentatively down and across his cheek, as if unsure of the path, so alien was the terrain.

We began words and abandoned them, floating silently in a moment I hoped could delay the inevitable. I thanked God for a gift that, in the distorted world of AIDS, I had wanted so badly over the years. I would outlive my father.

Only after having collected the courage before to say goodbye, to realize the fear and talk about it anyway, did I have the strength to address it with my dad.

This is not a story about AIDS. But it is a story because of it.

This article first appeared in The Advocate.