The music my friends liked when I was a teenager intimidated me. It was the head-banging rock of the early seventies, and it felt alien and unappetizing. Most of all, it just felt… straight, in a way I knew I could never be. Alone in my room, I listened to my beloved Broadway musicals, and resigned myself to the fact that popular music would never really speak to me.

And then in 1977, when I was sixteen years old, I began sneaking into the only gay bar in Shreveport, Louisiana. Inside I found joy and liberty, fashioned with bell bottomed pants and handsome smiles and the dance floor – oh my God the dance floor – centering the nightclub was a glorious explosion of colored light and swinging hips and arms reaching up, up to the sky as if we could clutch it in our hands. The music was an entrancing bombardment of sound, and one song, one mesmerizing invitation to touch the heavens, was played again and again.

It was Donna Summer. And she was singing “I Feel Love.”

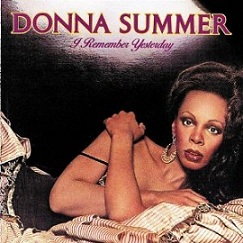

The track was really the triumph of producer Giorgio Moroder, who created the driving, synthesized beat that would define Donna Summer’s music for years to come. But I knew I had to own this amazing song, and soon I stood proudly at the record store cashier to buy my very first popular album, Donna Summer’s I Remember Yesterday.

The track was really the triumph of producer Giorgio Moroder, who created the driving, synthesized beat that would define Donna Summer’s music for years to come. But I knew I had to own this amazing song, and soon I stood proudly at the record store cashier to buy my very first popular album, Donna Summer’s I Remember Yesterday.

I had found my music, my voice, and my lifelong muse.

The following year I had come out as a senior in high school, and Donna Summer was still in her “whisper period.” It was never my favorite sound from her – it felt like playing chopsticks on a grand piano – and I knew from her other album tracks that she could let it rip. As I was graduating she did just that, with the release of her iconic “Last Dance.” Her full-throttle pipes were on stunning display. Dance parties would never be the same.

By the time I left home for college in New Orleans, the music of Donna Summer had exploded into popular culture. I felt so proud of her, as if I had discovered her myself. My nights in the French Quarter were spent in the Parade disco on Bourbon Street, dancing to “Hot Stuff” and “Bad Girls.”

The feeling of joyous exuberance that surrounded that disco is hard to describe. It was a sea of shirtless men, staking claim to our sexuality and the promise of infinite possibilities ahead. The incessant thump! thump! thump! of the beat was our clarion call, and it shouted Here! Here! Your tribe is here! We were so beautiful, in ways we were much too young to know.

And then soon, of course, the lights began to dim.

By 1982, I was struggling in Los Angeles as an aspiring actor, and Donna Summer was having a musical identity crisis. Record executives wanted a new sound for her to accompany the changing times, and her longtime producer Giorgio Moroder had been replaced by a succession of others. The red-hot Quincy Jones produced her Donna Summer album that year and their studio clashes became legendary. The album floundered and produced no significant hits.

At the Los Angeles gay pride festival the next year, I was thrilled to hear Donna’s voice again, sounding gorgeous and almighty, singing “She Works Hard for the Money.” I took to the dance floor but was somehow unable to muster the joy I had known only a few years before. Life had intervened. And it had brutal plans for the men under the dance floor tent.

At the Los Angeles gay pride festival the next year, I was thrilled to hear Donna’s voice again, sounding gorgeous and almighty, singing “She Works Hard for the Money.” I took to the dance floor but was somehow unable to muster the joy I had known only a few years before. Life had intervened. And it had brutal plans for the men under the dance floor tent.

Donna Summer produced dance floor singles, if not hits, in the years that followed, but we weren’t paying attention. The night club crowds dissipated, as a silent killer plucked men away one by one. AIDS had begun its murderous march through the gay community.

The villain wasn’t simply the disease in those darkest of days. It was ignorance, and the judgment that rose up from social conservatives who saw Godly retribution in the horrific deaths of our friends. And so, when Donna Summer became a born-again Christian during this period and announced she would no longer perform her early, erotically charged hit “Love to Love You, Baby,” her gay audience viewed her with immediate suspicion.

An ugly rumor began. Someone claimed to have heard her make a homophobic remark during a concert appearance. Depending on who was repeating the story, she had either said AIDS was God’s judgment, or that God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve. The unsubstantiated rumor swirled and grew, in an environment in which gay men were particularly sensitive to ignorance and hatred. By the time Donna Summer took it all seriously enough to set the record straight, it was too late. What was left of her popularity fell victim to the social maelstrom of AIDS.

I never believed the story, and defiantly continued buying her albums, though they appeared with less regularity. Donna Summer would have only one more true hit, “This Time I Know It’s for Real,” which I chose to perform for my maiden appearance in drag at an AIDS benefit. The fact that during this time Donna Summer was raising money for AIDS research gained little traction among emotionally bruised and unforgiving gay men.

I never believed the story, and defiantly continued buying her albums, though they appeared with less regularity. Donna Summer would have only one more true hit, “This Time I Know It’s for Real,” which I chose to perform for my maiden appearance in drag at an AIDS benefit. The fact that during this time Donna Summer was raising money for AIDS research gained little traction among emotionally bruised and unforgiving gay men.

Today, disco may be dead, but Donna Summer’s music laid the groundwork for everyone from Madonna to Lady GaGa, even if my body has found it harder to approximate the dance floor moves of my youth. But in my mind, as I blast “Dim All the Lights” in the privacy of my living room, I am young and powerful and life is making promises that are wonderful and possible.

Donna Summer is among the spirits now, joining the legions of ghosts haunting brightly colored discos from another era. She is still cooing to them, to these throngs of boisterous men, inviting them to the dance, where there is everything to celebrate and nothing to forgive.

The men are moving to the beat and laughing and holding one another. They are all beautiful, and they know it.

And they feel love.