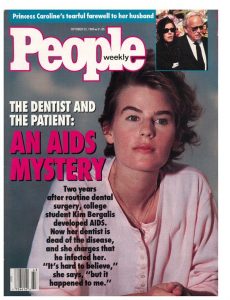

You probably don’t know his name, but you might have heard the name of his most famous “victim.” In 1990, dentist David J. Acer was accused by his patient, Kimberly Bergalis, of infecting her with HIV.

It was the start of an onslaught of accusations from Acer’s patients and an accompanying media frenzy. Acer was already extremely ill and in no condition to defend himself. Bergalis became famous, advocating for the rights of patients and testifying before congress before her death in support of a potential law to force healthcare workers to disclose their HIV status. The law did not pass.

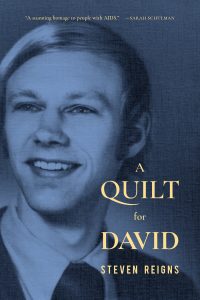

In his new book, A Quilt for David, poet Steven Reigns revisits the case after months of research throughout Florida, where the story took place. Reigns spoke to Acer’s family, friends, coworkers, and patients. What emerges is a stunning case of HIV stigma and the power it had to sway the public, our lawmakers, and even the pursestrings of malpractice insurance companies, all of it told in a poetic literary format.

I spoke with author Steven Reigns about his remarkable piece of “investigative poetry” and the legacy of David J. Acer — and Kimberly Bergalis — then and now. Our conversation has been gently edited for length and clarity.

Mark S. King: This is a perfect topic for me. I like new ways to tell the stories about what happened to us. I appreciate you reminding us of David J. Acer.

Steven Reigns: You’re welcome.

You were in 8th grade when Kimberly Bergalis made the news. I was working in the HIV field, and I remember thinking, when the accusations came forward, “the dentist did it.” That it was some kind of kamikaze mission by a troubled man with AIDS who was going to take some people down with him. And the media bought it exactly that way, too.

Yes. The words that we now use, like “allegedly,” the kind of words that buffer an accusation, were not used when talking about David Acer. It was very definitive language.

Not unlike, by the way, Gaetan Dugas, the man characterized as “Patient Zero” in the Randy Shilts book, And the Band Played On. He was vilified in the media, posthumously, only for us all to learn that Shilts’ editor thought the book needed a villain, and they re-framed Gaetan’s story to an outrageous degree. The Patient Zero narrative wasn’t true, factually or epidemiologically.

Sometimes when we’re given a narrative, we don’t question it. And unfortunately that’s what happened with Gaeten Dugas and it’s what happened with David Acer.

It’s a shame that I can mention Kimberly Bergalis’ name to friends in the AIDS arena and they recognize it, if not get a cold chill. But David Acer? Not so much. You have rescued him from the trash bin of history, as they say.

Queer people are still so despised and detested, a little less so now, so it’s not surprising people weren’t holding him, in this situation, in generosity. And Kimberly claimed to be a virgin, and Americans love a virgin. Actually, there was a medical report where Kimberly had venereal warts and that’s very uncommon for a virgin to have. It’s a sad situation for everyone involved. I feel for everyone.

It was hard enough, tragic and painful, to have died of AIDS in the early 1990s. But to have the media at your hospice door, asking ‘hey, what do you have to say about all these people you killed?’ I want to share with readers the only known statement from David on this matter, which you include in your book, written from his hospice bed at that time.

It is with great sorrow and some surprise that I read that I am accused of transmitting the HIV virus. I am a gentle man and I would never have intentionally exposed anyone to this disease. I have cared for people all my life and to infect anyone with this disease would be contrary to everything I have stood for.

What a plaintive plea from a dying man. How awful it must have been to live out his last days like that.

And also to go into hiding again. At the very start of his illness, he was going to doctors under aliases, because he was so scared of being found out. And then he was open to his family, and his parents moved down and moved in with him to tend to him. He had this short window of openness in his life, and then in the last moments of his life he was checking into hospice under an alias. As he wrote that statement from his hospice bed, a different name was on the door of the room.

That’s just one of the many interesting factoids in your book that stunned me. There are so many, and I urge people to read this book and discover them for themselves.

Each of Acer’s six accusers, as it turns out, had risk factors for HIV. Sex, intraveneous drugs, and blood transfusions. The dentist narrative seemed like an awfully convenient escape hatch for a closeted gay man who had contracted HIV, for instance. It’s easy to see the desperation of everyone involved, to hide out, to avoid blame, to not look like a whore. Everyone was trying to escape the stigma of HIV.

It might have felt really good for them to point their finger at someone, as opposed to blaming one’s own behaviors.

The whole episode feels like a precursor to HIV criminalization. This was a civil case, but the blame game is the same. And all six accusers got settlement money.

Yes, some more than others. Each of the first three accusers received a million dollars.

Kimberly Bergalis played the virginal victim — literally — to the bitter end, despite evidence you uncovered about her to the contrary.

Kimberly Bergalis played the virginal victim — literally — to the bitter end, despite evidence you uncovered about her to the contrary.

The book makes it clear, for anyone that needed clarity, that these women and supposedly heterosexual men were worth saving and advocating for, as opposed to the throngs of gay men dying alone.

Definitely. And look at the legacy of those involved. Kimberly Bergalis has a beach named after her. There’s a bronze statue of her in front of her high school.

Just think what might have been uncovered had anyone during that time put a fraction of your effort into getting to the truth. You spent weeks in Florida speaking to anyone you could, including former friends and co-workers of David and of his accusers.

AIDSphobia and homophobia permeated the research that was done at the time.

You bring up the profit machine that was created from AIDS hysteria, and this case in particular. Your book mentions the television ads to buy your own dental tools to take to your appointments, because we should all have those in our glove compartment, right?

So many people profited off this situation.

You’re a poet, and chose to tell this story using a poetic format. I was skeptical of this as I began your book because “investigative poetry” didn’t feel like a thing. But damn if you don’t bring out both the facts of the matter and the feelings of those involved.

You’re a poet, and chose to tell this story using a poetic format. I was skeptical of this as I began your book because “investigative poetry” didn’t feel like a thing. But damn if you don’t bring out both the facts of the matter and the feelings of those involved.

Thank you. One thing that was important to me is that I did not take any poetic licence.

Literally!

Yes. It is a story saturated with misinformation, that I didn’t want to add to it, by flourishing it with my own imaginings. I wanted people to know that what they’re reading, the details that are in this book, are from the research that I’ve done.

Two of his accusers are still alive.

Yes. I communicated with one of them, Lisa Shoemaker.

Does she still claim that David did it?

Yes. I think she’s a great example of how the press and the public treated her, who was honest at the time about her other risk factors, versus Kimberly Bergalis. Lisa worked for a carnival as a summer job, and she wasn’t offering the mythology that Kimberly was as a virgin. Actually, there was a man Lisa was involved with, and she discovered he had cheated on her with another man.

And yet Lisa still believes the dentist did it?

She had genetic testing at the time telling her so. In England, they don’t even use this particular test anymore because in maternity wards the tests between mothers and their own children weren’t matching up. So, the genetic testing they were using to attach David and his patients was faulty.

The tragedy of this story didn’t end with David’s death, or even Kimberly’s. A few years later, exhausted from the ordeal and facing financial struggles, David’s father shot himself in the backyard of the home he inherited from his son. Here you have this horrible fallout that just kept going and going.

It’s a terrible coda to his story.

But, for anyone who still wonders, this case is closed. The dentist didn’t do it. I believe that. This is all just a stunning example of HIV stigma.

Yes. I believe that’s true.

Mark