It was 1975 and I was 14 years old, all gangly limbs and stubborn acne, and I was sitting in the passenger seat of a parked car. Splayed across my lap was the magazine, open to the page my companion had selected. I was staring at the photo with something like revelation.

“I wasn’t sure if I should show this to you,” he said. He was a little nervous. “But I think it’s wonderful.”

He had the exquisite name of Pericles Alexander, and was once the arts critic for The Shreveport Times, my hometown paper. Now, in his retirement, he had found a willing pupil in me, a teenager that loved working on summer musicals while secretly grappling with my own emerging sexuality.

Pericles was a kind mentor, nothing more. He drove me to local plays and regaled me with stories of Broadway actors and theatrical gossip. We would huddle together in the dusty seats of our community theater, me hanging on to his every whispered word as the house lights dimmed for the latest production.

When he parked his car in front of my family’s house that night after a show, he quietly pulled the magazine out of a plain brown envelope. He thumbed through it while I watched, suddenly nervous about what the pages might reveal, and then he handed it to me. I set the magazine in my lap and my eyes quickly grew the size of serving platters. Never in my young years had I seen anything as startling as the image before me.

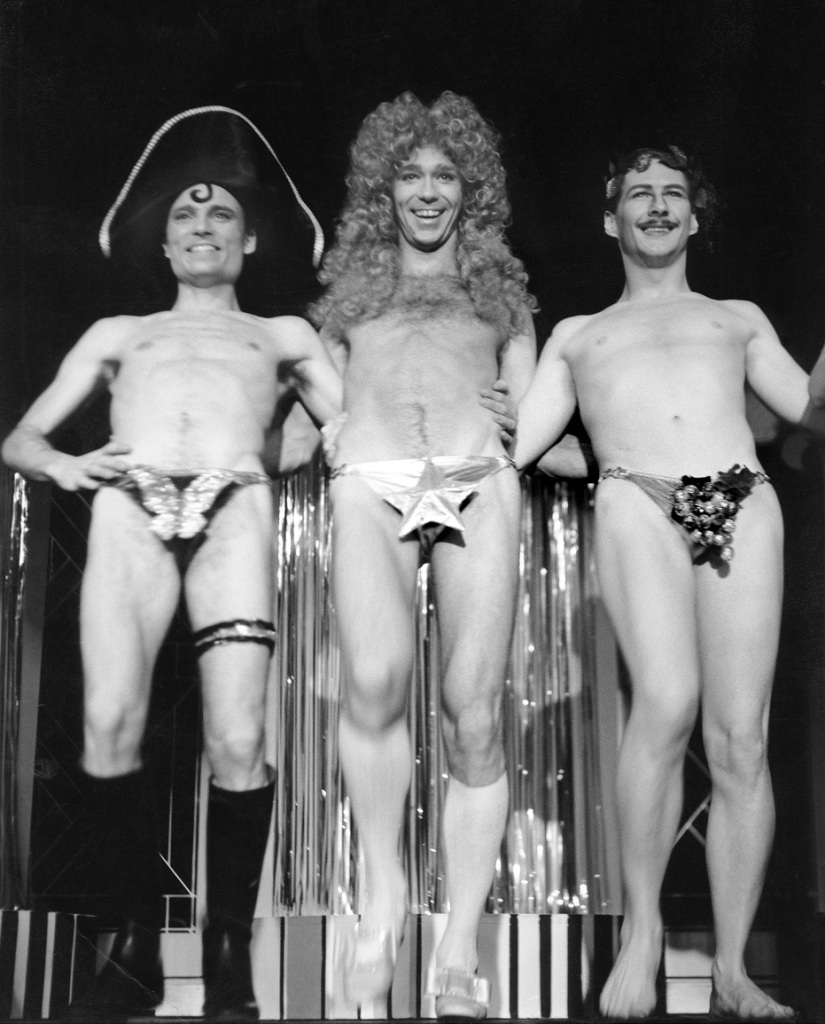

There were men in the midst of a musical production number of some kind, and they were all nearly naked. Among them, the unmistakable and familiar face of a man, grinning buoyantly, with nothing but a bedazzled butterfly the size of the palm of my hand covering his crotch.

That man, the one with the rhinestone butterfly as a makeshift jock, was my older brother, Richard. And he looked triumphant in his grand pose.

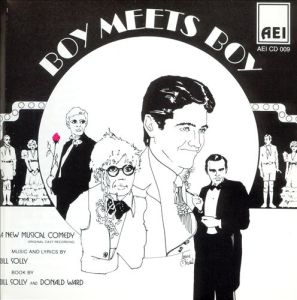

I forced my eyes away from Richard and scanned the page for an explanation. The article was about Boy Meets Boy, an off-Broadway sensation set in the 1930’s that adopted the spirit of an old Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musical. Except that, in this story, there were two Fred Astaires and no Ginger Rogers.

My brother is in a gay musical in New York City, I marveled to myself. My brother is nearly naked. My brother is in a glossy magazine. My brother is nearly naked.

“Are you alright?” Pericles asked.

“Sure,” I said tentatively, and I flipped the magazine over to its cover. The Advocate, it said. The National Gay Newsmagazine.

I had never heard of such a thing. My own struggle to accept myself was purely internal, and often in conflict with nearly everything I witnessed or read growing up in Louisiana. My southern instincts suggested the magazine must be perverse, but something inside me knew better.

And my mind was still trying to process that photo of my brother, captured in an outlandish moment, yes, but performing on stage and doing what he loved. Even if he had never mentioned the show to me during one of his phone calls from New York, much less come out to me.

Richard and I weren’t close, not yet. He was fifteen years older and had left home to pursue his acting dreams by the time I was a toddler. Many years later we would both find ourselves living in Los Angeles and that gave us the chance, finally, to carve out a loving friendship as adults. But in that moment, as I sat in that car in the dark, Richard was simply a happy gay man frozen in an outrageous pose of defiance and joy.

“I think appearing off-Broadway is really impressive,” Pericles offered. “So I thought you would enjoy this. But… maybe you better not take this inside.” He gently slid the magazine from my grasp. He returned it to the brown envelope and tucked it beside his seat.

“Sure, okay,” I answered, and I reached for the door. My head was swimming. “Thanks, Pericles. Yeah. I’m excited for him.” And that much was true.

I trotted inside and gave my parents a report about the play I had just seen, parroting the review Pericles had given me on the ride home. And then I went upstairs to bed.

I slept soundly that night, my dreams filled with theater and music, butterflies and rhinestones, and an unfamiliar but comforting emotion. It felt like the inauguration of a special kind of pride.

Mark

(I was invited to write this for a special issue of The Georgia Voice by its new editor, Darian Aaron. Darian is killing it down there in his new position. — Mark)

PLUS…

Even with so-called “permanent fillers” to treat facial lipoatrophy (facial wasting), the product loses a percentage of its volume over time. So, whenever I am in southern Florida I pay an occasional visit to Dr. Gerald Pierone to let him adjust me a bit, as I did earlier this month (that’s Dr. Pierone at right, in his new Orlando satellite office, with his assistant Aime Evans). The topic remains the thing I am asked about most often because facial wasting affects so many long time survivors of HIV, and I want to be transparent about the fairly dramatic change in my face over the last years. You can watch Dr. Pierone’s treatment — and see the striking before and after photos — by checking out my video blogs of my treatment.

Even with so-called “permanent fillers” to treat facial lipoatrophy (facial wasting), the product loses a percentage of its volume over time. So, whenever I am in southern Florida I pay an occasional visit to Dr. Gerald Pierone to let him adjust me a bit, as I did earlier this month (that’s Dr. Pierone at right, in his new Orlando satellite office, with his assistant Aime Evans). The topic remains the thing I am asked about most often because facial wasting affects so many long time survivors of HIV, and I want to be transparent about the fairly dramatic change in my face over the last years. You can watch Dr. Pierone’s treatment — and see the striking before and after photos — by checking out my video blogs of my treatment.