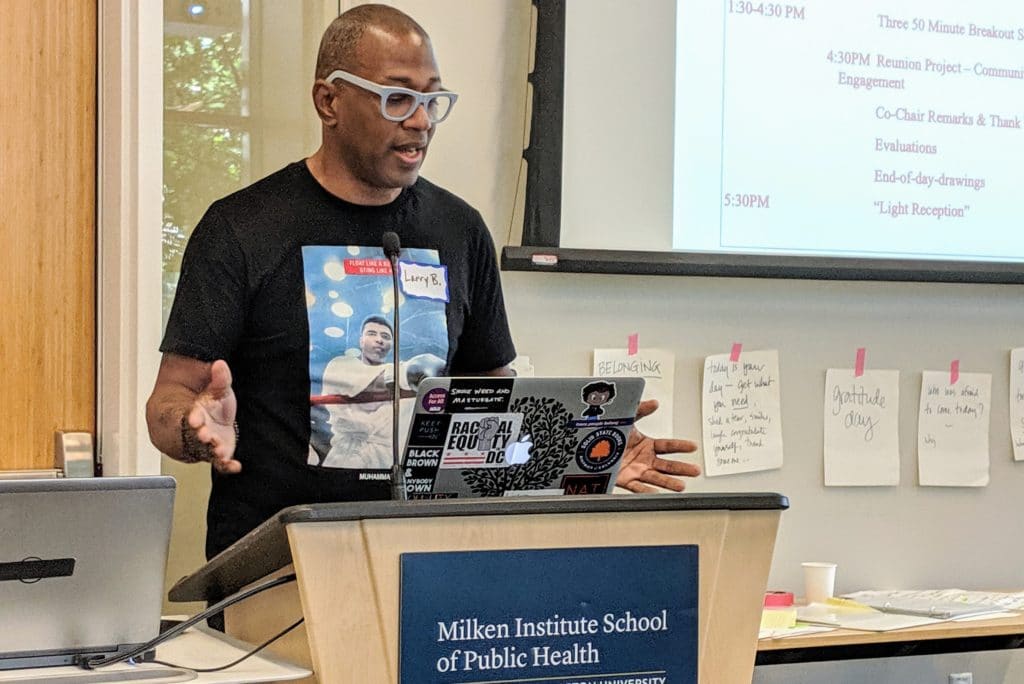

For many years, I have viewed activist Larry Bryant, Jr. as one of the most highly regarded voices of conscience in the HIV/AIDS movement, and among Black men in particular. At the recent Reunion Project event in Washington, DC, a day of education and community for long-term survivors, Larry laid bare his life with HIV and his observations from decades in the HIV arena.

Larry does not mince words. He calls out other community figures when he sees fit. He names names. He exposes racism and transphobia, even among our ranks. His keynote speech taught me, shamed me, and maddened me. That’s good. The HIV community could use some righteous anger and serious reflection, and far more than we have exhibited lately.

Here are the full remarks from Larry Bryant, Jr., at the Washington DC Reunion Project event on June 22, 2019:

On World AIDS Day in 1994, the venerable Black AIDS activist Mario Cooper released a blog post that cautioned all of us to ‘take a deep breath, [and] let it out slowly’ as he was about share his opinion about what was wrong with the AIDS movement at the time.

Mario went on to talk about what he described as exhaustion within the AIDS community and groups around the country, including the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power, or more commonly known as ACT UP, seemed to be moving away from the mic, literally.

Cooper wrote that during an ACT UP meeting in New York City, writer David B. Feinberg, “barely out of his hospital bed and suddenly missing 25 pounds, expressed his profound anger and frustration over ACT UP’s loss of energy.” Cooper continued that even Larry Kramer “snatched up the microphone and implored ACT UP to refocus” before being voted out of order and storming off with a shout: “ACT UP is dead. ACT UP is dead.”

By the way, all of this was a good two years before Andrew Sullivan wrote his first piece announcing the end of the AIDS epidemic – for him. His announcement was largely framed by his public and economic status and access to newly available antiretrovirals and combination therapies that, for him, and other primarily White gay men with means, that yes, the epidemic could be called over. However, in that year of 1996, what about the rest of us?

Larry Bryant, Jr., and DC Reunion Project committee members Bishop Rainy Cheeks, Donald Burch, Marcia Ellis, Ron Swanda, Beri Hull, Derrick Cox, Linda Scruggs, and George Kerr III

Ok, so now in 2019 let’s all take another deep breath, and let it out slowly, again. I am going to give another man’s perspective on where we’ve been, where we are, and where we’re going.

When I was kid, from the first time I put on a football helmet, I wanted to be a professional football player. By the time I arrived at high school across the Potomac at TC Williams, I idolized shut down cornerbacks like Lester Hayes and Mike Haynes. And after winning a Virginia State Championship in 1984 on one the best high school teams in the country, and one of the best ever in Virginia, I hoped that my college experience would give me the chance to get to that level.

And for a little while, it did. I was among the nation’s leaders in interceptions and on my way to becoming an All American as a freshman. I was certainly on the path toward what I had dreamed of before putting on the green and gold at Norfolk State University. And despite being a football star on the field I was also still dealing with the challenges of depression and anxiety and just being a freshman away from home for the first time. And the following Spring would bring far different and debilitating challenges.

I was diagnosed as living with the antibodies to the virus that cause AIDS early in 1986 – the term HIV positive did not yet exist in Norfolk Virginia at that time. I was also given, at the most, eight years to live based on the current science of the day regarding diagnosis and life expectancy of someone in my condition.

Basically, at 18 years old I was diagnosed to die without much options for treatment or for living. However, the desperation only began there.

Parallel to my own personal disintegration was the rise of crack addiction and gun violence in Norfolk, here in DC, and other predominantly Black communities around the country, turning young men into dust. Drugs and violence emanating from a rage-filled generation of young Black men knowing the truth that a Reagan-Bush United States had no interest in saving them – providing jobs, providing viable health options, providing hope.

This is where the HIV & AIDS epidemic was born in Black America. And young men and women like myself in the District stared feverishly in the face of a local and federal government that refused to even speak the name of an epidemic that was rampaging among those most vulnerable.

It reminds me of quote from Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man: “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorting glass. When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves or figments of their imagination, indeed, everything and anything except me.”

It also reminded me that this is a world, this is a country that hunted down, coerced and terrorized, then wrongly convicted five young men in New York City in 1989 for crimes they didn’t commit – for no other reason than being young, male, and Black. Why would I think that things would be any different here in DC?

This city didn’t have time for me, my blackness, or my HIV. This feeling was at the core of my severe depression that forced me to drop out of college, off the football team, depart from my dreams, and lead to not one but three suicide attempts.

Still, as some people pronounced the end of an epidemic for them after being among the first in line for treatment and care, statistics began to emerge of the apocalyptic impact the virus had among Black, Brown, and immigrant communities in this city and across America with Black women leading the way in new infections in the early 90’s. The AIDS epidemic had begun to resemble the impact of economic, education, and overall health disparities that we see regularly here.

We know those numbers. We know those disparities. And the response the AIDS epidemic at that time began to resemble the ‘rescue’ response this city has always had for Black and Brown communities – slow (if at all), ineffectual, and ultimately, not close to what is needed.

And let’s be real, the HIV & AIDS organizations in DC as well as cities and towns elsewhere perpetuated much of this ineffectual response. People living with HIV & AIDS were, and still are, often counted in numbers but not yet seen as complete, whole people.

Sure, the HIV & AIDS community has had much to celebrate and has grown in many ways since the 90s and early 2000s. For example, I’d like to think that we’ve come a long way since 2006 when a group of Black women in south Florida representing themselves and the Campaign to End AIDS were yelled at by a fellow World AIDS Day marcher, a White Gay man who told them to go and get their own disease, because they had come and taken theirs.

I’d also like to think that we’ve evolved from hearing Paul Kawata lecturing National Association of People With AIDS board members about choosing between being more like the NAACP or the Black Panthers, implying that in his view there are ‘proper’ ways we should act as activists and advocates and not rock the boat – reminiscent of the yanking of Larry Kramer from the stage.

I’d like to think that we in the HIV and AIDS community — many of us who have been or are still experiencing blatant racism, sexism, transphobia, and homophobia, or just experiencing outright disrespect and dismissal — would be the bridge builders for those who will carry this fight to its end. Yes, to the end of this epidemic.

And with all this talk about intersectionality, as the old folks in the room we need to be more comfortable in that intersection ourselves, meeting and greeting others where they are. Advocating for life solutions, not just HIV specific solutions.

By the way, many of us have been around here sitting at the table for way too long not allowing other voices, experiences, and perspectives to be heard and seen. We have to realize that the end of AIDS, and the end of all that comes with this epidemic, goes far beyond just acquiring your meds and treatment. The stigma and ignorance surrounding this disease still cuts like a knife to the jugular, and even more so when it comes from within the community we all hope to find refuge, solace, connection, logic, understanding, and love.

Again, Mario Cooper wrote in 1994 that, “we fail to recognize that the manner in which America responds to AIDS is an indicator of its value of our lives. The converse is also true: how we respond as a community is an indication of how we value ourselves.” That second part is what stings most even when the first part is predictable. That second part stings because still at times we are our worst enemy.

So, how do we move forward? Where do we, in DC and beyond, go from here? Sitting smack in the middle of several DC Councilmember’s and Mayor’s elected term and on the precipice of what’s going to another loud and combative Presidential campaign cycle, we need to begin mounting a comprehensive, coordinated campaign that targets both incumbents and political hopefuls.

How will they address the social, economic, and structural factors that will end this epidemic once and for all? Our collective effort would allow us to develop a strong base for challenging the radical attempts to end government-funded AIDS efforts and programs, including expanding harm reduction programs, sex and sexuality education for school aged children, and affordable permanent and supportive housing.

We need to reinvigorate a local and national grassroots effort like the Campaign To End AIDS, or locally, like DC Fights Back, that prioritizes the voices of people who are living with HIV and AIDS. These networks should again provide that training and leadership development of those same individuals so that they are not continually tokenized and shuttled like cattle from one conference to the next for funders and grant obligations.

These networks should be supported by, not obligated to, local and major AIDS organizations. These grassroots networks should be organized like a political campaign. Locally, this grassroots network should use modern polling and targeting techniques that will allow us to create a savvy communications effort to remind DC residents and their representatives in the Wilson Building the importance of these issues.

We need to re-engage the mainstream media. The waning of coverage by local networks and newspapers has undercut our ability to keep our most pressing issues in the public eye. Included should be social media campaigns, local radio networks regular blog posts or editorials.

We must actively and meaningfully bring new allies to the table. The HIV and AIDS community still marginalizes young voices, transgender voices, and ex-offender voices. There are still divisions among race, gender, and education. Those who live and love different than us should not be written off as allies or even leaders.

Locally, a grassroots mobilization that can motivate and focus on our entire community in DC is sorely missing. This can only be created by building, at the neighborhood level, an organizational structure that allows for broad and informed participation. Groups can focus on their respective Ward and Councilmember, meeting with them regularly, holding them accountable when they are slow to act, praising them when they are on point.

Look, we are all tired. We are all getting older. And, at least with me, I awake most mornings frustrated and impatient, much like Mario did in the early 90s, looking at a dysfunctional AIDS community struggling to be effective in a dysfunctional America, a dysfunctional DC.

However, we can still impact our future as well as those coming after us. None of this happens overnight. And though as much has changed since the 80s and 90s and even through the 2000s; my hairline, my waistline, for example. One thing remains and will always be true – AIDS will not be over until it is over for everyone.

Thank you.

(Larry Bryant, Jr. is the field organizer for the ACLU of the District of Columbia. I have included links to groups mentioned by Larry in his text whenever possible, and urge you to learn more about them and become involved, or seek out similar groups in your own community. – Mark)