(This essay appears in my collection of essays, My Fabulous Disease: Chronicles of a Gay Survivor, available now at online outlets or your local bookstore.)

“Did I ever tell you about the night that Emil died?” my brother Richard asked me. It was 1992, and AIDS had taken Richard’s lover a full three years earlier. The death ended a love affair that had lasted more than a decade.

I cocked my head. “Well, I was there, Richard, so I mean – ”

“You were there after,” he said, and downed his drink. “Don’t you wonder what it was like just before?” He asked the question nervously, a perfect match for the cigarette he held in one hand — a long broken habit, suddenly resumed — and the cocktail in the other, which had been requested shortly upon his arrival to my apartment.

“You were there after,” he said, and downed his drink. “Don’t you wonder what it was like just before?” He asked the question nervously, a perfect match for the cigarette he held in one hand — a long broken habit, suddenly resumed — and the cocktail in the other, which had been requested shortly upon his arrival to my apartment.

“It’s not like I was trying to keep it from you, Mark,” he said, and he offered the glass for replacement. It was an odd thing for him to say.

I walked to the kitchen and unscrewed the vodka bottle, beginning to feel nervous myself. Richard talked as I cracked an ice tray.

“Emil had one of those lines that went way in inside him…” He was beginning a story I wasn’t sure I wanted to hear.

“A hickman,” I said.

“Yeah,” he answered, and he reached for the drink while the ice was still twirling. “But something was wrong with it the night before. It was swelling. So we took it out.”

I returned to the couch. Richard paced.

“The next morning the nurse came and Emil was being stubborn. He didn’t want the new Hickman.” He gulped his drink and took a breath. “I got an inkling what he was up to when the nurse said ‘Emil, starving yourself is not a pretty way to go.’ But Emil kept saying, ‘no, no, I won’t do this!’ and I remember he looked so weary, Mark. Just exhausted.”

This isn’t the visit I planned, I thought to myself. I meant for my brother to see the new ceiling fan I had installed. But my handiwork couldn’t compete with the story that was now rumbling out of him.

“I walked the nurse out and went back to Emil. He reached up for my hand, and he said, ‘you knew that today would be the day, didn’t you?'”

Richard looked at me but didn’t acknowledge what must have been a growing expression of shock on my face.

“I knew Emil wanted me to say yes, so I did. But inside I was screaming ‘NO! NO!’ ”

Richard stopped, and I found the silence torturous. “Well,” I said, “it sounds like he was, uh, in charge of himself.”

“Oh, he was in control all right,” he responded. “He told me to go get the book. The one about how to kill yourself.”

Richard’s next few remarks would be lost on me. I couldn’t get past The Book.

“So I’m reading him the chapter we had picked out,” Richard was saying, “and it suggests washing down the pills with alcohol. We had some Seconal and I found some Scotch.”

I knew about assisted suicide but had never heard of the mechanics of it firsthand, or considered the logistics a caring lover would undertake — or had witnessed the haunted result like the one that now sat chain smoking across my living room.

“I made some toast for him just like the book said,” he continued, “and while we waited for him to digest the toast I opened the capsules and put the stuff into a glass.”

I imagined my brother sprinkling powder into a glass while Emil looked on. I wondered what kind of small talk that activity encouraged.

“I poured the scotch, a couple of good-sized shots, and he wanted it right away.” His voice trailed to a whisper. “I wanted him to wait, to wait, to wait… I wanted to hug him. I wanted to do it right, you know? But he kept reaching for the glass, and I would say, ‘no, Emil, wait, please wait, I want to say I love you again…’”

Tears were filling Richard’s eyes. His hand shook, knocking his glass loudly on the coffee table as he set it down and brought his hands to his face.

And even so, he went on.

“Emil downed the glass in one gulp and made a face, and then he just laid back on the pillow. It took about twenty minutes.” Richard looked up at me and managed a sad grimace. “Emil always said that when you go, you go alone. I hated that for him. I wanted him to feel me there, you know? So I held his hand real tight…”

I stared at my brother. Tears now streamed from his face. His eyes conducted a dazed search around the room as they tried to focus on something, anything that would bring some comfort or clarity.

I couldn’t tell what I was feeling about this. Was it pity? Was it shock? How many kinds of pain can we distinguish within our soul?

“The book said to wait twenty minutes after his heart stopped, you know, before calling the doctor. I kept leaning over him and trying… trying to hear his heart. But I couldn’t because my own blood was pounding in my ears! And those next twenty minutes…”

“What were you doing…” I asked, startled by the sound of my own voice, “during those twenty minutes?”

“Screaming,” he said simply.

Silence engulfed my apartment, surrounding the word.

I put my arm around him and he continued to weep. Please be all right, I thought. Please be happy again, Richard. My brother. My brother.

He received my embrace but his heart had taken distant refuge. It had long been numbed by the effects of the spent cocktail glass, sitting impassively on the coffee table, occasionally clinking with the sound of shifting, melting ice.

Mark

NOTE:

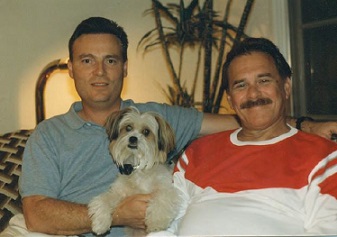

This post is adapted from A Place Like This, my chronicle of life in Los Angeles during the dawn of the AIDS epidemic. (Photo above: Richard, left, and Emil in 1986.)

Suicide was a common feature of life for gay men in the 1980’s. But rather than it being a result of bullying or despair, with which it is often associated today, it was very often a gesture of empowerment for embattled AIDS patients wanting to die on their own terms, sometimes with the assistance of those who loved them most.

Our elderly have always shared these mortal intimacies. Assisted suicide has even been institutionalized with the common use of a morphine drip in hospitals and hospices, which calms the patient and, when increased to certain levels, hastens death by shutting down the body.

As for Richard, he has recovered from his loss 25 years ago and lives happily today in our home town. “I often think of that night, and consider my feelings about it,” he told me recently. “I can honestly say I don’t feel even a twinge of guilt. I have plenty of regrets, but not about that.”