The lobby of the Melbourne convention center at the international AIDS conference last July was packed with scientists, community educators, and activists. I was busy wrangling interviews for my daily video blogs.

Across the room I spotted JoAnne Keatley and Laxmi Narayan Tripathi, two of the most visible transgender women in the world and experts on transgender issues. I scurried up to them for a sound bite on their thoughts about the conference.

Across the room I spotted JoAnne Keatley and Laxmi Narayan Tripathi, two of the most visible transgender women in the world and experts on transgender issues. I scurried up to them for a sound bite on their thoughts about the conference.

“This has been quite a year for trans people,” I began, as an ill-conceived question began forming in my tiny brain, “what with the visibility of trans people like actress Laverne Cox. That must help a lot, huh?”

The women stared at me as if I were mad.

“Our visibility is due to grass-roots organizations doing the hard work of education and advocacy,” JoAnne responded with a gracious but cool reserve. She went on to explain that transgender people face enormous challenges just to make ends meet financially. “We are victims of discrimination and violence on a daily basis,” she said. “Too many of us, in order to survive, have to engage in sex work. The number one intervention for the trans population is to make it safe for us to participate in the workplace.”

I felt like an idiot, but my insensitivity knew no bounds and I wasn’t done yet. The activists were accompanied by a third woman who was quite lovely but declined contributing to the interview. As I thanked JoAnne and Laxmi for their time, I turned to their companion and good-naturedly said, “ah, the quiet, pretty one.”

Because the real litmus test for a successful trans person is whether or not they are attractive.

The women were already walking away, presumably to find someone who could avoid insulting them, when JoAnne glanced back to pointedly call out, “we are all pretty!”

I like to consider myself an enlightened gay man. A career in HIV advocacy has taught me a lot about sexuality, racism, and women’s issues. But I’ll be damned if I have managed to learn very much about the T in LGBT, despite the issue bubbling up throughout popular culture. My sensitivity level is long overdue for some transitioning of its own.

Transgender people throughout the world may not know who Bruce Jenner is either, but it appears the former Olympian is about to grant many of us another such teachable moment. The gold medal winner and famously reluctant participant on the Keeping Up with the Kardashians reality show is the subject of numerous media reports that (s)he is transitioning – I don’t even know at what point it is customary for the pronoun to change – and there will be a special series on the E! Network devoted to it, including visits to physicians and mental health professionals.

Transgender people throughout the world may not know who Bruce Jenner is either, but it appears the former Olympian is about to grant many of us another such teachable moment. The gold medal winner and famously reluctant participant on the Keeping Up with the Kardashians reality show is the subject of numerous media reports that (s)he is transitioning – I don’t even know at what point it is customary for the pronoun to change – and there will be a special series on the E! Network devoted to it, including visits to physicians and mental health professionals.

If handled with sensitivity – admittedly, a tall order for the network that brought us the Kardashian clan – Bruce’s story has the potential to provide an educational lesson not unlike Magic Johnson’s coming out as HIV positive in 1991: an American sports hero, someone many of us think we know, revealing a private part of themselves to a public woefully ignorant on the topic. Oprah must be chomping at the bit.

Easy does it. While it may be true that Bruce is ready to share his story, transgender people face enormous physical and mental challenges even after their transition, including continued risk of suicide, and their stories are singular and vary widely. Let’s hope Bruce has supportive counsel and is braced for the media barrage.

All this in a year that has seen the Amazon series Transparent win awards and the President say the word “transgender” for the first time in a State of the Union speech, and not long after Chaz Bono shook his groove thing on Dancing with the Stars.

I have sincere enthusiasm for these developments yet still find myself judging those who would be advocates, placing the likes of Laverne Cox, imbued with a winning I’m-just-happy-to-be-here spirit, in stark contrast to the more confrontational author and activist Janet Mock, who beneath her high wattage smile looks like she is inches away from slapping the stupid out of somebody.

God forbid transgender people make us uncomfortable. You know, like liberated women once did, and gay rights protesters and marchers in Selma and AIDS activists.

How difficult it must be for an entire segment of humanity to contend with score keeping like mine, to be judged by whomever spoke up last, to be seen as a monolithic “community” without nuance, to have to continually respond to dangerous ignorance without losing it completely.

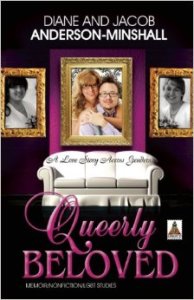

My curiosity about all things trans was largely satisfied recently by reading Queerly Beloved: A Love Story Across Genders by married couple Diane and Jacob Anderson-Minshall. It is a remarkable tale about their former lives as a lesbian couple and what happened when they were faced with the realization that one of them, Suzy, is a transgender man who would eventually take the name Jacob.

My curiosity about all things trans was largely satisfied recently by reading Queerly Beloved: A Love Story Across Genders by married couple Diane and Jacob Anderson-Minshall. It is a remarkable tale about their former lives as a lesbian couple and what happened when they were faced with the realization that one of them, Suzy, is a transgender man who would eventually take the name Jacob.

There are revelations on every page of Queerly Beloved about issues I have wondered about and even more that have never occurred to me. Diane and Jacob chronicle every step of the transition and never make the reader feel like an inappropriate voyeur.

And trust me, the journey is a labyrinth of sexual and gender identity, as questions about being lesbian or straight, male or female, are raised in increasingly complicated permutations. These questions are all the more urgent to Diane and Jacob, given their careers as feminists working in the lesbian publishing arena.

Jacob is bracingly candid about his initial doubts about his transgender status and the couple’s misgivings about losing their identity in the lesbian community. However freeing his masculine transformation may have been, he does not shy away from the reservations that accompanied it and the ramifications he faced afterward.

Jacob includes fascinating insight into the riddle of nature vs. nurture, including the numbing of emotions he experienced when testosterone treatment began and how, in his new identity as male, he found himself in the foreign, privileged fellowship of men — and realized he was suddenly deferred to by women. Ultimately, Jacob challenges us to think again and again about what it means to be male.

For her part, Diane achingly shares her confusion and heartbreak over losing the woman of her dreams to his transition and hormone therapy, and writes of her lover’s femininity slipping away in ways subtle and profound: his unwillingness to talk through feelings as he once did, the light touch of his hands being replaced by a thicker skin, literally, and a numbing of emotions that robs him of his highs and lows.

In a particularly telling scene, they both attend a book reading where a gay man who came out late in life describes the impact on his former wife. The sad and rueful glance that Diane gives Jacob during the reading makes you realize that, whatever the nature of the coming out process, there are often unintended casualties in its wake.

Diane and Jacob reveal in intimate detail what we may have long suspected. Masculine and feminine are a continuum, intersecting both our gender and sexuality, and the enormous world we inhabit contains gradations of it all.

Diane and Jacob reveal in intimate detail what we may have long suspected. Masculine and feminine are a continuum, intersecting both our gender and sexuality, and the enormous world we inhabit contains gradations of it all.

Yet, as the book’s title makes clear, this is a love story. And despite confused presumptions from family and friends about the nature of their relationship and even their sex life, the couple continue to find joy and satisfaction in the arms of the same person they have adored from the very beginning.

Although they go to great lengths to patiently answer questions in their inspiring memoir, the love Diane and Jacob have for one another is the final, simple answer.

Let that be a lesson to us all.

Mark