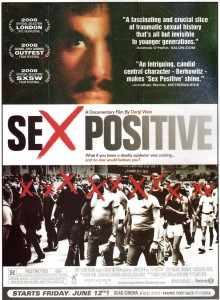

The New York City of 1979 shown during the opening minutes of Sex Positive, the documentary now available on DVD, is awash in gay sexual liberation. Male couples strut their stuff arm in arm, sporting biker jackets and cocky mustaches and bulges in their denim that strain credulity (no fashion era has ever screamed “gay porn” like this one). It’s an almost quaint snapshot, in retrospect, taken just before the arrival of a major buzzkill in the form of a murderous pandemic.

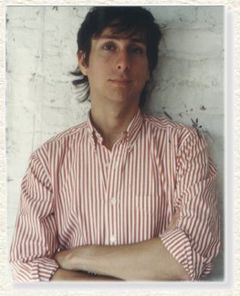

Cruising amid the happy sleaze was gay S/M escort Richard Berkowitz (pictured, right), the man who would quickly and unwittingly become known as the “self hating enemy of gay people.” And all because, the documentary contends, he tried to save their lives.

Cruising amid the happy sleaze was gay S/M escort Richard Berkowitz (pictured, right), the man who would quickly and unwittingly become known as the “self hating enemy of gay people.” And all because, the documentary contends, he tried to save their lives.

Today, Berkowitz remains in the apartment where he once entertained masochistic clients (the hardware they once dangled from is still in evidence in the doorways), and during our phone interview his emotions ranged from joyful gratitude to angry resentment, all displayed with an engaging but steely force of will. Here is a man still trying desperately to be heard and understood.

“I’ve been smeared, censored and attacked over the years, as evidenced in the film, by gay men who either don’t like me or don’t like sex workers, or people into S/M, or anyone who questions AIDS orthodoxy,” he said.

And here is why. In the early 1980’s, as AIDS deaths mounted but before the HIV virus had been identified, there was no known cause for the mortality. Was there a single, possibly viral culprit, as gay activist Larry Kramer and others believed, or was there a collection of factors having to do with the promiscuous gay lifestyle, as Berkowitz suspected?

Berkowitz based his views on talks with his physician, Dr. Joseph Sonnabend, and another Sonnabend patient, singer Michael Callen (pictured, left), all of whom were ready to vocalize something heretical: the promiscuous lifestyle of gay men was contributing to the emerging epidemic.

Berkowitz based his views on talks with his physician, Dr. Joseph Sonnabend, and another Sonnabend patient, singer Michael Callen (pictured, left), all of whom were ready to vocalize something heretical: the promiscuous lifestyle of gay men was contributing to the emerging epidemic.

“Everything Michael and I said and did in regard to AIDS came from Sonnabend,” Berkowitz tells me. “Callen and I knew nothing about science or sexually transmitted diseases when AIDS began. Sonnabend taught us how to educate ourselves, and Michael and I tried to teach that to gay men.”

Dr. Sonnabend had a medical practice in the heart of the ultra gay Chelsea neighborhood, and he had made a connection between some of his gay patients’ propensity for the fast lane and their risk for developing AIDS symptoms. This seemingly basic fact wasn’t easy for the trio to disseminate.

In 1982, Berkowitz and Callen wrote an article in the New York Native entitled We Know Who We Are: Two Gay Men Declare War on Promiscuity. In it they claimed the New York gay scene — bars, baths, drugs, poppers and all — had birthed the growing epidemic, and only through behavioral change could it be contained.

In 1982, Berkowitz and Callen wrote an article in the New York Native entitled We Know Who We Are: Two Gay Men Declare War on Promiscuity. In it they claimed the New York gay scene — bars, baths, drugs, poppers and all — had birthed the growing epidemic, and only through behavioral change could it be contained.

This infuriated gay intelligentsia like Larry Kramer, who believed that both freshly minted gay pride and mainstream assimilation were threatened by Berkowitz’s talk of queers as bath house sluts. “He felt promiscuity was too dangerous to talk about in front of straight people,” Berkowitz says today. “But Callen and I said ‘fuck straight people, gay men are dying and AIDS is preventable.'”

The film’s tag line, “What if you knew a deadly epidemic was coming, and no one would believe you?” is a stretch, considering Berkowitz wasn’t the only one worried about the gathering storm. Most every gay bar patron at the time shared his sense of dread, and it was clear to Kramer and others that a public health crisis was at hand. The question was how to address it.

Berkowitz and Callen addressed it by writing, under the supervision of Sonnabend, the 1983 pamphlet “How to Have Sex in an Epidemic: One Approach.” It is widely considered the invention of safe sex as we know it today, and uncanny in its detailed instructions of avoiding transmission through bodily fluids.

And it turned out that Berkowitz and Kramer were both right: the HIV virus was identified later that year and is now considered the single cause of AIDS, while the guidelines Berkowitz outlined to prevent transmission remain valid. “I was wrong to dismiss there being a new virus that was central to AIDS,” he now says. “There are still people who won’t forgive that.”

And it turned out that Berkowitz and Kramer were both right: the HIV virus was identified later that year and is now considered the single cause of AIDS, while the guidelines Berkowitz outlined to prevent transmission remain valid. “I was wrong to dismiss there being a new virus that was central to AIDS,” he now says. “There are still people who won’t forgive that.”

Such inescapable sadness hangs over Sex Positive — all those dying men, all that existential confusion — that the arguments between the opposing schools of thought seem secondary. After the film revisits the third or so public television debate between Kramer and Berkowitz/Callen, one wishes they’d just shut up and do something.

And of course, they did. Kramer not only wrote searing, groundbreaking theater such as The Normal Heart, he was also among the founders of ACT UP and The Gay Men’s Health Crisis. His status in gay history is iconic. Callen became the gay face of AIDS, singing at events, writing for The Village Voice and appearing in the film Philadelphia before his death in 1993.

The intervening years for Berkowitz (right) have been less kind. The film outlines his descent into drug abuse, and even his old ally Sonnabend describes Berkowitz as becoming “useless” for a time. Berkowitz resents the portrayal and has no interest in contrasting his life with that of Callen, who now has a New York City health center bearing his name.

The intervening years for Berkowitz (right) have been less kind. The film outlines his descent into drug abuse, and even his old ally Sonnabend describes Berkowitz as becoming “useless” for a time. Berkowitz resents the portrayal and has no interest in contrasting his life with that of Callen, who now has a New York City health center bearing his name.

“Do people dismiss the Beatles’ music or Robert Downey’s acting because they were using (drugs)?” he asks. “The only thing I ever wanted was not to die before I had lived a full life and finished what I felt the universe had put me here to do. With Sex Positive, I feel I’ve crossed the finish line. I got my happy ending.”

Perhaps not entirely. The safe sex guidelines he created were co-opted by public health officials and quickly sanitized to make them palatable to a general audience, and Berkowitz regrets his “skewed portrait” in the documentary. “The movie shows me in relation to the safe sex debate and my battle with addiction. But my 54 years add up to much more than that! I just regret being pushed out of safe sex discourse, because I had something to contribute.”

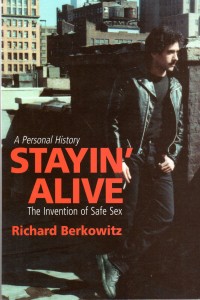

He hopes to contribute again. His 2003 book, Staying Alive: The Invention of Safe Sex is back in print, and he wants to keep speaking and developing his web site and blog. It may help alleviate the fact Berkowitz struggles financially, living on disability and handouts from former clients.

He hopes to contribute again. His 2003 book, Staying Alive: The Invention of Safe Sex is back in print, and he wants to keep speaking and developing his web site and blog. It may help alleviate the fact Berkowitz struggles financially, living on disability and handouts from former clients.

“It would be nice to have money, but I’ll take being alive over cash,” he says. “Riches come from having a purpose in life.” Moments later, he betrays his complicated thoughts on the topic. “I’m dismayed by comments in ‘Sex Positive’ that I didn’t do enough. I did a lot, and it’s not like anyone ever paid me!”

Thanks. Credit. Payment. After days of being haunted with sadness by viewing Sex Positive, the reason for its melancholy spell struck me. There could never be enough thanks, for Berkowitz or unknowable others. No one can quantify the payment due. How could the efforts of so many ever be calculated? How might proper credit be dispensed?

Whether it was Berkowitz outlining safer sex guidelines or countless men and women caring for dying lovers, valor was impossible to measure during what felt like the end of the world. Few may ever know the bravery of Berkowitz, or Callen, or Kramer.

Or me. Or you.

And with HIV rates rising among gay men again, Sex Positive underscores how much work, how terribly, frighteningly much, there is left to do.

Mark