There’s more room in a broken heart.

— Carly Simon, “Coming Around Again”

When Will Armstrong emerges from heart surgery in just a few days, he will have weeks of hospitalization ahead. He will also have expensive new hardware in his chest and a devoted animal waiting anxiously at home.

What he will not have is a pulse.

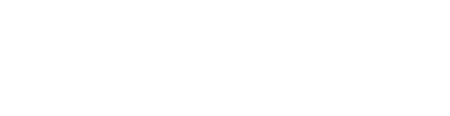

Will, a 44-year-old living in Atlanta, is having a Left Ventricular Assist Device (LVAD) implanted, and it will push the blood flow through his heart so smoothly that the throb of a pulse will be virtually nonexistent. Unlike a pacemaker, the LVAD needs electricity to function, provided by a battery pack to be carried by Will at all times. With an extra battery always on hand. And a couple more charging at home.

The last year may have been devastating for Will, but the process has had an unexpected effect on his emotional state.

“I’m happier than I was before I got sick,” Will says now. Allowing himself to receive the love and support of his wide circle of friends has had an enormous impact. “A lot of people will never know that kind of love while they are alive,” Will says. “To be able to know that is an incredible gift.”

The bearded weight-lifter has always cut an imposing figure, and he admits he used his physicality as armor while navigating life as a gay man. “I had to project this image,” Will says. “It was such a fraud.” His intimidating posture kept people at a distance, even as he struggled with life events that called out desperately for support.

Will tested HIV positive twenty years ago. Coming to terms with the stigma attached to the virus is something he managed to resolve some time ago, until he found himself facing another disease that posed a more immediate threat: crystal meth addiction.

Once he began a recovery program for meth addicts, populated largely by other gay men, Will was surprised to learn how many of his fellow addicts were also HIV positive but uncomfortable saying so. “That surprised me,” he says, “that people could feel stigmatized for their HIV, even among other gay people in recovery.” Will responded by becoming one of the founders of Pozitively Fabulous, an annual retreat weekend for people in recovery living with HIV, now in its fifth year.

As his years of successful recovery passed, however, Will continued to hold tight to his ultra-masculine persona. His social media pages were littered with gym selfies and bicep measurements. It was an unhealthy fixation on self, Will now admits, and it eventually caught up with him.

In May of 2015, after seven years of clean living, Will relapsed on meth for two full weeks.

“I ended up in the emergency room,” he says. “I thought I was having panic attacks, but I was in kidney failure. I was in total disbelief when they diagnosed my heart failure. I’ve never even had high blood pressure.”

“It could have been anything, HIV, diet pills, steroids, crystal meth, genetics,” Will says. But he knows that, when it comes to addiction, the most obvious answer is usually the right one. “People will sometimes say how ironic it is that I ‘escaped drug addiction’ and then this happened. No. I didn’t escape drug addiction. This is what happened.”

What has followed is a year of medical trial and error, as doctors tried to keep Will’s heart viable while exploring alternatives. He has been denied a heart transplant due to HIV, and his doctors say there are no heart transplants happening in the United States for people with HIV, anyway (the very few organ transplants that are happening, such as liver transplants, are between HIV positive patients and donors).

“I went through a couple months where I didn’t want to live anymore, I was suicidal,” Will says. “I didn’t want to be here anymore.”

And this is where Addie comes in, the “creature more spiritual than anything in my life,” says Will.

And this is where Addie comes in, the “creature more spiritual than anything in my life,” says Will.

Addie is the pit bull that is glued to Will’s side, constantly vigilant for a hug from him or signs of a treat or a walk. “Addie is the reason I’m still here. I live alone, I’m single, I didn’t have a boyfriend or the fabulous life I thought I would have. But Addie forced me to get up every day and take her out. She’s the reason I stuck around.”

“When I met her at the dog rescue two years ago, they told me she was hard to adopt because she was high strung and not great around kids or dogs.” Being a pit bull probably didn’t help her chances, either.

It was a match made in shelter heaven. Both Will and Addie might have been outwardly intimidating to others, but what they really needed was some unconditional love. “I connected with her and fell in love,” said Will. “When I’m with her, I try to be as happy as she is. She is always right here in the moment, and she believes everything will be okay. She adores me. I’ve never had this type of relationship with anything.”

Will has a team of friends at the ready as he mentally prepares for the five-hour LVAD surgery in a few days, but he wants them to be focused on Addie, who will miss him terribly. “She is too big and hyper to sneak into the hospital to see me,” Will said, “but I’ll be doing video calls with her.”

Will has a team of friends at the ready as he mentally prepares for the five-hour LVAD surgery in a few days, but he wants them to be focused on Addie, who will miss him terribly. “She is too big and hyper to sneak into the hospital to see me,” Will said, “but I’ll be doing video calls with her.”

Will has watched YouTube videos of the surgery (“gruesome stuff”) and knows the risks of complications. He understands the LVAD will probably be attached to him for the rest of his life (“batteries are important, but I can plug myself in anywhere, including the car”). Whatever anxiety Will may be experiencing is blanketed by a deep sense of gratitude.

“Today, I look at situations that really should aggravate me, and I’m just not there. All that shit I thought you should think about me doesn’t matter. Things like money and romance aren’t important to me now, or being super macho so people don’t think I have feelings. What is important to me are things I already have.”

“My biggest challenges have been readjusting my expectations,” Will adds. “Sure, I have a lot of uncertainty in my life, but I’ve got so much love the last year from my friends and family. And you know what? I allow people to love me. They want to be helpful, and the biggest thing I can do for them is let them love me.”

As Will considers his close brush with mortality this year and the recovery process ahead, he sounds like a man who is comfortable, at long last, in his own skin.

“I’m grateful I have been given a year to resolve things, let things go, take care of things,” Will says. “If I were to leave this planet, I would be okay with that. I’m okay if it’s my time.” His affairs are in order, including a new home for his beloved Addie, just in case.

“All that said,” Will offers finally, “I don’t want to go.”

Mark

(Will Armstrong passed away on Friday, March 25, 2022, surrounded by his sisters and friends.)