“There were people who displayed remarkable courage then. People who lived and died by their promises and shared the intimacy of death…”

— Once, When We Were Heroes

My brother Richard would later refer to it as a “command performance.” It was 1989, and he had phoned me after weeks of frustrating silence about the declining health of his lover Emil. Richard said that Emil wanted to see me. “Tonight,” he said. Charlie, my partner at the time, and I walked through their front door within an hour.

Richard led us to the sofa in the den where what looked like a mountain of blankets had been piled. I looked toward the blankets, and Emil’s head — small, ancient and childlike at once — peered out. A curved brass reading lamp reached over Emil’s face, casting a dramatic yellow glow across his forehead and onto his face.

Richard led us to the sofa in the den where what looked like a mountain of blankets had been piled. I looked toward the blankets, and Emil’s head — small, ancient and childlike at once — peered out. A curved brass reading lamp reached over Emil’s face, casting a dramatic yellow glow across his forehead and onto his face.

It was as harsh as the fluorescent strips I had often seen above the hospital bed of so many dying friends — shining straight down, showcasing the sickness beneath. Who lights these guys? I wondered absently.

“Hey there, Emil,” Charlie said. “How’s it going?” I had learned not to lead off with a remark like that.

“Hello, Charlie,” Emil said weakly. His voice was a strained breath that worked without the cooperation of vocal chords. He looked shrunken.

Emil proceeded to express how much he had valued our friendship. “…and Mark,” he breathed out, “I want to tell you how much I appreciate you giving that blood for me…”

It had been an experimental treatment for people with AIDS, giving them the blood of people who were HIV positive and healthy. It was nothing, really. Sixty minutes of my life. Like so many promising treatments, it didn’t work.

“It was easy, Emil, really –”

“Nevertheless,” he interrupted, willful to the end.

The blankets moved slightly, and Emil produced a tiny, aged hand from them. It trembled slightly as he motioned to Richard, who acknowledged the signal and left the room. Charlie and I sat there wondering what more to say, finally surrendering to the silence.

Richard returned with an envelope and placed it in my hands. A lovely parting gift? I thought, astounded.

I smiled toward Charlie and noticed that Richard and Emil were without expression, lost in their silent, exhausted daze. I opened the envelope and pulled out a $100 gift certificate to Macy’s. Charlie and I looked at the paper admiringly, and I said how thankful I was.

Richard managed an almost perfectly horizontal smile, and I knew at once he was the one who bought it. I thought of him driving across town for the item, on strict orders from Emil to purchase the certificate and from what store, and Richard wondering if his lover would be alive when he got back.

Emil cast sleepy eyes on Richard and I knew it was time to leave. I leaned forward toward Emil and barely brushed my hand across the blanket as a farewell. Richard led us out, and stood on the porch as we drove away. I watched him close the front door. The porch light blinked out.

We drove through the lovely, tree-lined streets of their neighborhood with our mouths half opened, with words begun and then abandoned. Only after driving for miles did I succeed in delivering a full sentence.

“So, Charlie,” I said, realizing I still held the envelope tightly in my hands, “how do you think we should spend the gift certificate?”

Two nights later we would find ourselves on their sofa again, in circumstances far more grave. Charlie and I were bleary-eyed from the chaos that had begun with Richard’s phone announcement an hour before, delivered with stunned clarity, that Emil had died.

We were in the den where we had received the gift certificate only days before, but Emil wasn’t there. He had spent his last days in the master bedroom, by Richard’s side. Charlie turned to the windows behind us and pulled the blinds away. We could hear a vehicle approach.

“Don’t,” I said. “We shouldn’t. We better not look.” He released the blinds and the car — or hearse, or coroner’s truck — drew nearer and was now chugging just outside the window, just beneath us and beside the front steps.

We stared at each other, dissecting every sound, and then knowing when Emil was being taken. We heard wheels, barely squeaking across tile floors, rolling out of the master bedroom toward the front door. A heavy door opened and then closed. I wanted to pull the shades wide open and see for myself, and I didn’t dare.

The vehicle changed gears and began the retreat down the driveway. We held our breath as it drove slowly down the hill and faded away.

Richard walked in to the den and we sat up straight. Just shut the hell up Mark, I said to myself. Don’t start talking now because you’ll just screw it all up.

Richard asked me to stay the night, and Charlie went home to await further instructions. Richard and I didn’t stay up, didn’t talk much at all. He went to bed and I feel asleep on the couch.

I was awakened in the morning by Richard’s voice. He was on the phone across the room, speaking to someone culled from the worn pages of an address book he held cradled in his lap. I quietly rolled over and watched him. He was beyond the grasp of any healing embrace.

Every call began the same, with his weary hello and then saying he had some very bad news. And then he would say it out loud. Emil had died. It was something he had been terrified of ever saying, but that now would be repeated a dozen times on the morning of his lover’s death. He usually made it through the first minute or so, but then would be barraged with condolences and have to say “thank you” and “yes, he certainly was” and “I know he is no longer in pain” a few times during each call. And it was that part that would break him, until he convulsed again into sobs and his goodbye would be hard to understand.

He would sit there and catch his breath, finding the next name in the address book through teary eyes, and then pick up the phone again. And again.

It is one of the most powerful images of my brother that I have.

I sometimes dream of it.

Mark

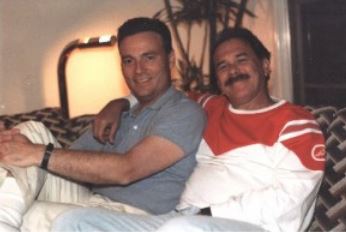

(This is adapted from my book, A Place Like This, about the dawn of the AIDS epidemic in Los Angeles. I am so grateful for our progress since then, but also feel strongly about sharing the truth, and the intimacies that we experienced as a community during the darkest years. Scenes like the one above are still playing out — 7,000 gay men die of AIDS in the United States every year. Pictured above are Richard (left) and Emil. — Mark)