In 1977, I ran for senior class president, hoping against hope that my penchant for wearing platform shoes and fellating men in my spare time might somehow get overlooked by my high school classmates in Bossier City, Louisiana. I lost that faith when my campaign signs throughout the school hallways were vandalized. As the student body arrived that morning we were greeted with the word “FAG” scrawled across the posters in red spray paint.

Trying to comfort me, our student counselor Mrs. Berry gave me some advice. “When you put yourself out there in a position of leadership, you open yourself up to… criticism.” She stumbled over her word choice, unsatisfied with it, but I knew what she meant.

Still, a dozen posters with “FAG” painted on them seemed a little harsh.

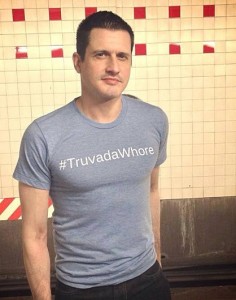

That lesson isn’t lost in the treacherous and very adult arena of gay sexual politics and PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis, or preventing HIV infection using the drug Truvada). Speaking up in favor of the prevention strategy often leads to being labeled as anti-condom or simply a barebacking slut. So much for the complexities of modern HIV prevention.

That lesson isn’t lost in the treacherous and very adult arena of gay sexual politics and PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis, or preventing HIV infection using the drug Truvada). Speaking up in favor of the prevention strategy often leads to being labeled as anti-condom or simply a barebacking slut. So much for the complexities of modern HIV prevention.

And then there’s the dark excesses of the internet age, in which people are symbols, hardly human at all, and serve only as place holders for a polarizing issue to be judged and dissected. It’s the contemporary version of red spray paint, obliterating the individual in favor of a single, cruel label.

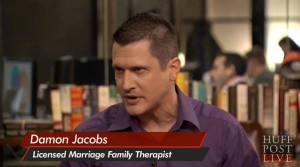

One might expect Damon L. Jacobs, then, who has proferred himself to the world as a gay man using PrEP, to be a little bruised and resentful after two years of constant media exposure — and vulnerable to the name calling and labels thrust upon him. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Damon, who has spoken openly and sometimes explicitly about his sex life before and after PrEP to everyone from Huffington Post to The New York Times, takes the criticism and his accelerated celebrity all in stride. “It’s not personal,” he told me, referring to those who criticize the use of Truvada and his engagement in particular. “They don’t have any idea who I really am. Some anonymous people behind a keyboard do not matter.”

Instead, Damon believes we are in the midst of a community-wide teaching moment, so long as we do it carefully.

“We can’t underestimate the role of fear,” he said, suggesting his expertise as a New York therapist with a private practice. “For years, we have had to live a certain way by using condoms or die. Then suddenly things change. That’s where the attacks come from. Their belief system is threatened. I think attitudes are genuinely changing — the last year or so a lot of people have changed their views — but they have to go through a transition for that to happen. And they must be respected during that process.”

Although public scrutiny this intense is new for Damon, advocacy on behalf of gay men’s health is not. For years, Damon worked on behalf of an HIV vaccine trial, becoming a regular presence in the New York gay club scene to spread the word about enrollment. He continued the work even after opening his own therapy practice.

By the time the vaccine trial was discontinued in early 2013, Damon had been privately taking PrEP for nearly two years. After having heard about early, encouraging results of PrEP research — and facing the fact that he wasn’t using condoms as often as he once had — Damon talked to his physician and started taking Truvada independently long before it garnered FDA approval.

It was a prescient move on his part, but not a choice he had been discussing openly with the many gay men with whom he had been in contact through his vaccine work. A drag queen changed all that.

Damon had worked with her during his bar outreach about the vaccine trial, and when they crossed paths again he mentioned he was taking PrEP. “What’s that?” she asked. When he explained it, her face “just dropped,” he said.

“Why didn’t you ever tell me about this?” she asked him. “I just tested HIV positive.”

“No one was getting the message out,” Damon told me. “Not public health, not HIV organizations, not on social media. Nobody.” When Damon began a Facebook group about PrEP in July of 2013, the response was nearly immediate. “Things snowballed,” he said.

What followed has been a firestorm of newspaper, television and online coverage of PrEP, often using Damon as a personal illustration. By participating, Damon has had to discuss the most personal aspects of his sexual life, including his growing reluctance to use condoms consistently, being a receptive sexual partner for whom exchanging semen has meaning and, perhaps most heretical after a generation of fear and mortality, the importance of pleasure and satisfaction in our sex lives as gay men.

What followed has been a firestorm of newspaper, television and online coverage of PrEP, often using Damon as a personal illustration. By participating, Damon has had to discuss the most personal aspects of his sexual life, including his growing reluctance to use condoms consistently, being a receptive sexual partner for whom exchanging semen has meaning and, perhaps most heretical after a generation of fear and mortality, the importance of pleasure and satisfaction in our sex lives as gay men.

“Pleasure and death have been one in the same,” he said. “For so long, pleasure could only result in something tragic, rather than seen as something important and powerful. To challenge that belief system, we need to have patience and compassion and empathy.”

Transparency about our sex lives — as they actually are, in the real world — has always been key in understanding behaviors and crafting HIV prevention messages. Moral debates only benefit the virus. But Damon’s honesty has enraged many gay men for “promoting” choices that are viewed as irresponsible and even dangerous. He responds to those attacks with his usual calm and a unyielding personal philosophy.

“I’m a student of A Course in Miracles,” he says, referring to the self-help curriculum popularized by Marianne Williamson in the 1980’s. Williamson was also very active in the earliest response to AIDS in Los Angeles. “I’m here doing God’s work,” Damon says simply. “And that work is to promote love in this world. I don’t usually talk about this, but I want to help people reduce fear. Depression, drugs, suicide, and even attacks on me, they’re all manifestations of fear.”

Honestly, I had expected to find an advocate more battered than this one. I was interested in the toll such constant scrutiny might take on a man. But Damon surrenders only the merest suggestion of the challenges of such explicit and public honesty.

“Most of the feedback about my work around PrEP has been great,” he said. “But a lot of hate and aggression has been unprecedented. It’s not the level I am used to. But I can sleep. A lot of people who stand up for love are going to be attacked.”

My high school campaign posters, a painful memory some forty years behind me, came again to mind. And in the calm of Damon’s convictions, those signs, dripping in spray paint, began to lose a great deal of their damaging power.

Mark