There must have been something in the water at those New York City ACT UP meetings back in the day. There had to be. The band of ferocious, cheeky AIDS activists (immortalized in the Oscar-nominated documentary, How to Survive a Plague) has produced scientists, novelists, playwrights, and two MacArthur Genius Grant recipients.

.

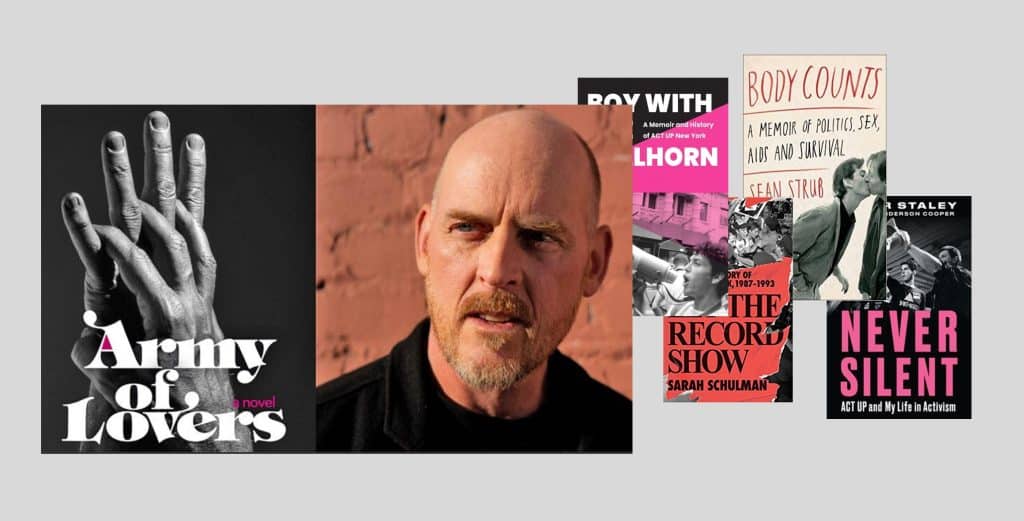

The crowded spate of ACT UP memoirs is quickly approaching a genre of its own, which is remarkable considering the New York chapter only numbered a couple hundred core members in its 1990s heyday. The books include Sean Strub’s politically focused memoir, Body Counts; Peter Staley’s chronicle from the center of the AIDS activism maelstrom, Never Silent; Sarah Schulman’s settling of scores and re-centering of women, Let the Record Show; and Ron Goldman’s personal account of his time as the group’s “Chant Queen,” Boy with the Bullhorn.

The latest entrant takes a decidedly different approach. In Army of Lovers, writer K.M. “Karl” Soehnlein transforms his lived ACT UP history into fiction.

At the Saints & Sinners LGBTQ Literary Festival in New Orleans last month, I sat down with Soehnlein to discuss fiction as the vehicle for a real-life story, the challenges of independent publishers, and how old arguments among ACT UP members can still erupt all these decades later.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Mark S. King: Your book, Army of Lovers, came out last October and yet it slipped through the cracks for me. Only here, at Saints & Sinners, am I catching up with it. This often happens, of course, with niche books or imprints. That must be frustrating for you.

K.M. “Karl” Soehnlein: I think that it’s just part of the territory when you are working in independent publishing. You get a lot of care and input as a writer, but a lot of the major outlets don’t give the time of day to a small publisher. So that means I work hard at getting the word out myself. Are there frustrations all the time? Yes. But after working on it for so long, the fact the book is out there, that people are reading and responding to it, feels like gravy.

I think there’s an interesting conversation to be had about your choice to make this fiction. You have this fascinating, heroic life story but then you chose to camouflage it. I want to know why.

One person’s camouflage is another person’s interior design. In memoir you feel more of a burden to adhere to the facts.

But you did change factual information to suit the thrust of the story.

I did, but I drew lines around things that I wouldn’t allow myself to change. The basic timeline, and important dates of ACT UP demonstrations. I wasn’t about to mess with that.

What is the advantage for the reader? How do we benefit from your lived story becoming fiction?

People like stories that are shaped by the properties of fiction. Suspense, tension, the building of a character arc over the course of a story. You’re getting a novelist’s rendering of history. I’m shaping it. I’m giving myself permission to create emotional drama on the page, to create conflict.

It sounds like I’m confronting you about your choice. Maybe I’m working through my own stuff here. I write first-person almost exclusively, including a lot of memory pieces. But if I’m being honest, I make up shit all the time. In my memoir, A Place Like This, I blur the lines of what I saw, how I felt, and who said what. It is my memory of events.

Yes.

Author K.M. Soehnlein at the Hotel Monteleone during the 2023 Saints & Sinners LGBTQ+ Literary Festival.

We’re kind of in the wake of two big ACT UP book releases last year, being Peter Staley’s Never Silent and Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show.

And to that I would add Ron Goldberg’s Boy with the Bullhorn. Ron’s book is written for Fordham University Press, so it’s an academic book and it’s footnoted and indexed and heavily vetted, more so than a memoir like Peter’s or an oral history like Sarah’s. So we’ve all got a different version of how to tell the story.

Several of the ACT UP books, including yours, open with a demonstration. Sean Strub’s Body Counts begins with the Stop the Church protest. Never Silent begins with the New York Stock Exchange action.

When you’re writing about an activist group that specializes in civil disobedience then it makes perfect sense. I opened with a protest in Albany, the capital of New York, over Mario Cuomo’s lack of HIV funding. It was small. We were having a die-in outside the doors of the State legislative chamber but they weren’t there. Somebody tipped them off. So, I’m showing the heroic, world-changing events that ACT UP did, but some days you’re going to die in front of an empty legislative chamber. There was often absurdity to it.

And some protests were hilarious. Bitingly so.

Oh yes.

And now we’re awash in these memoirs. It’s as if everyone needed twenty years to process what happened before they were ready to write about it.

I agree with that, and I think there are other things involved. It takes a while for it to come back around into the public consciousness again. I also think there is a whole generation of young adults who are curious about this.

There is a now-infamous conversation that occurred onstage in New York City last year between Peter Staley and Sarah Schulman, in which things got really testy about the accuracy of their respective books about ACT UP.

I was there. It was Peter’s book release for Never Silent, and he asked Sarah (Let the Record Show) to be in conversation with him. In the lead-up to the event she let him know that she didn’t like a lot of the things in his book, so we knew there would be some conflict.

And?

Sarah said there were misrepresentations in his book, and Peter had points of contention about her book. Interestingly, one of the issues that came up was around a clinical trial in the early 1990s that involved pregnant women living with HIV. This was the very clinical trial that caused a lot of conflict within ACT UP at the time. A lot of people blame it for the diminishment of ACT UP as a potent force.

Yes.

And that same clinical trial was being re-argued in the room that night, and not just between Peter and Sarah, but by other people there…

There were a lot of ACT UP veterans there.

There were. And some of the things that were unresolved in ACT UP came back to the surface. We were all together again, on the occasion of these books being published, and there were strong opinions coming right back up in the room that night. A woman sitting in front of me, not a ACT UP member, turned to me afterwards and said, “I feel like I’ve just been to an ACT UP meeting.” Now, if it had been an ACT UP meeting in 1990, we would have all gone out for a beer together afterwards, but instead I think people didn’t hang out.

It sounds like a family reunion and somebody brings up that one damn topic that pisses off everybody.

I use the metaphor that we were all in a war battalion together and some of us still think we should have taken that hill and others think we should have gone around the back way. We’re all still trying to figure out what happened in that battle that day.

And you’re shell shocked.

We all are. And I think that’s also what surfaced in the room that night with Sarah and Peter. PTSD. We watched so many people die. We worked so hard to keep people alive, and we failed as much as we succeeded. And we’re kind of old now, at reflective points in our lives, and there’s a lot to work out.

I’m glad you’re working it out in this book, and discussing it here with me today. We need all these perspectives from that time, and hopefully they meld together into something that is universally true.

We need to keep doing it, as queer writers. Our stories can be told in any way we like. And don’t let anyone tell us that, “oh, we’ve already heard about that.” No, they haven’t heard the full orchestra of voices.

Thanks so much for adding yours.

You’re very welcome.