When I was 15 years old, I couldn’t wait to attend a local community theater production of The Boys in the Band. I was intrigued by the play’s dark and mysterious reputation, and had heard that it included a lot of homosexuality (funny how that word isn’t used much anymore). It sounded like exactly what this budding young queer needed: some lessons about the yellow brick road ahead.

I didn’t like what I saw. The characters, a group of gay men celebrating a birthday, were mean and sad and angry with one another. And they were all presented like weird, exotic animals, bitching and crying for the lascivious thrill of a very shocked audience in Shreveport, Louisiana. I left the show feeling terribly disenchanted, fearing my life was destined to be drunken and pathetic.

I didn’t like what I saw. The characters, a group of gay men celebrating a birthday, were mean and sad and angry with one another. And they were all presented like weird, exotic animals, bitching and crying for the lascivious thrill of a very shocked audience in Shreveport, Louisiana. I left the show feeling terribly disenchanted, fearing my life was destined to be drunken and pathetic.

It was the theatrical opposite of an It Gets Better video.

In the insightful and appropriately melancholy new documentary Making the Boys, the remarkable journey of the groundbreaking play and movie adaptation is discussed by playwright Mart Crowley and a host of gay cultural voices, old and new.

When The Boys in the Band opened off-Broadway in 1968, homosexuality was still classified as a mental illness. The play’s behind-the-scenes peek at gay men in their natural habitat was fascinating to audiences and greeted with enthusiasm from the gay community. Yes, they were maladjusted, self hating fags, but they were our maladjusted, self hating fags.

When The Boys in the Band opened off-Broadway in 1968, homosexuality was still classified as a mental illness. The play’s behind-the-scenes peek at gay men in their natural habitat was fascinating to audiences and greeted with enthusiasm from the gay community. Yes, they were maladjusted, self hating fags, but they were our maladjusted, self hating fags.

But in 1969, as the movie version was being filmed only blocks from the Stonewall bar, a riot occurred at the club in response to constant police harassment. The modern gay rights movement was born. Seemingly overnight, New York gays stood up for themselves and demanded some respect — from others and, more importantly, themselves. By the time the film version of The Boys in the Band opened in 1970, the story and its sad characters felt like a politically incorrect relic. We wanted nothing to do with these old, bitter friends anymore. They didn’t reflect our “pride.”

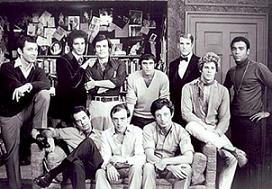

Opinions about the show vary wildly, as evidenced by the interviews in the documentary. Gay playwright Edward Albee (“Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolfe?”) always hated the show and still does. The surviving actors (the theatrical cast all recreated their roles for the film) staunchly defend the humanity of their characters. And younger gays interviewed about the show have no idea what the hell we’re talking about. “I don’t really know about any boys in the band,” states perplexed fashion star Christian Siriano. “Honey, I’ve got dresses to make!”

The Boys in the Band has become a litmus test for how you view our ability to love ourselves. And those boys continue to reverberate and reflect our attitudes and tribulations as gay men, and that includes the AIDS crisis.

Watching the film today, I’m struck with an odd compulsion. I see these characters laughing and bitching, and I want to reach through the screen and shake them and warn them, to tell them about something coming, something too awful to describe, of a plague they can’t possibly comprehend that is coming to kill them all.

Watching the film today, I’m struck with an odd compulsion. I see these characters laughing and bitching, and I want to reach through the screen and shake them and warn them, to tell them about something coming, something too awful to describe, of a plague they can’t possibly comprehend that is coming to kill them all.

Indeed, at one point in Making the Boys, we are shown photos of the actors, of the men who played these iconic characters we loved and then hated and then, finally, simply accepted. And listed under each of the actors’ names is the year he died of AIDS. 1984. 1985. 1988. On and on it goes, through what appears to be a majority of the cast.

The moment brings about such emotional confusion, of regret and interrupted affections. It’s like hearing of a death of a long lost friend with whom you had a troubled relationship.

Our boys continue to live on through the film, performing their roles on that screen exactly the same way, defiant in their stereotypes, no matter how many times we revisit the movie.

What has changed, for better and for worse, is us.

Mark